Almost 600,000 people die every year in México, nearly half of them as a result of chronic illnesses such as heart and lung disease, diabetes, HIV or cancer.[35] Hundreds of thousands more Mexicans battle with earlier stages of these and other chronic illnesses. Over the course of their illness many of these people experience debilitating symptoms such as pain, breathlessness, anxiety and depression. To ensure proper medical care for many of these individuals access to palliative care and pain medicines is essential. Without these services, they will suffer needless pain and distress undermining their quality of life and that of their families in their final days of life.

Over the course of our research, we collected testimony from dozens of patients and their families about the challenges they faced accessing palliative care. While a few patients reported having access to comprehensive palliative care, the overwhelming majority of patients had no access to palliative care whatsoever or accessed care only with great difficulty, delays or with frequent disruptions.

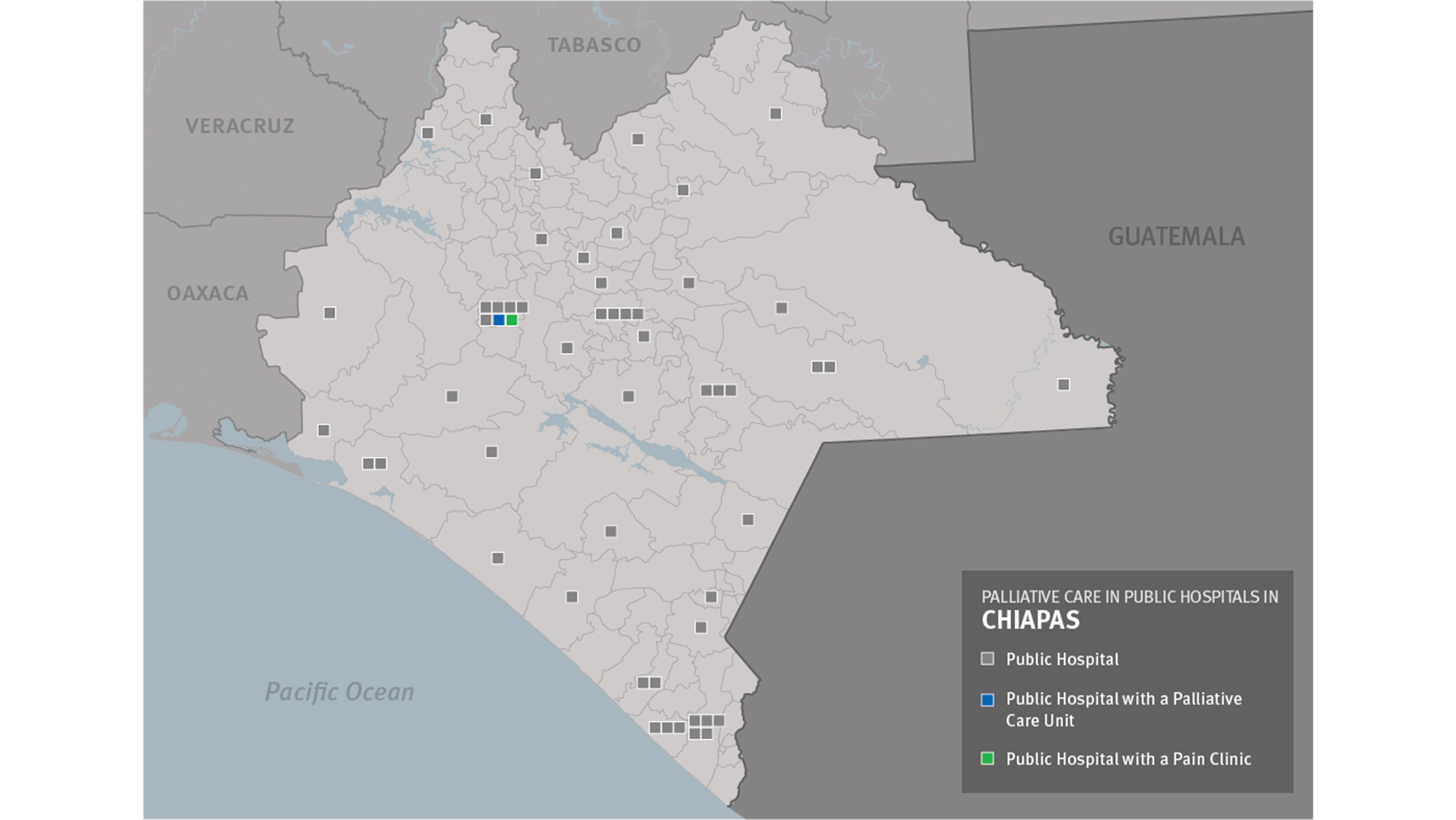

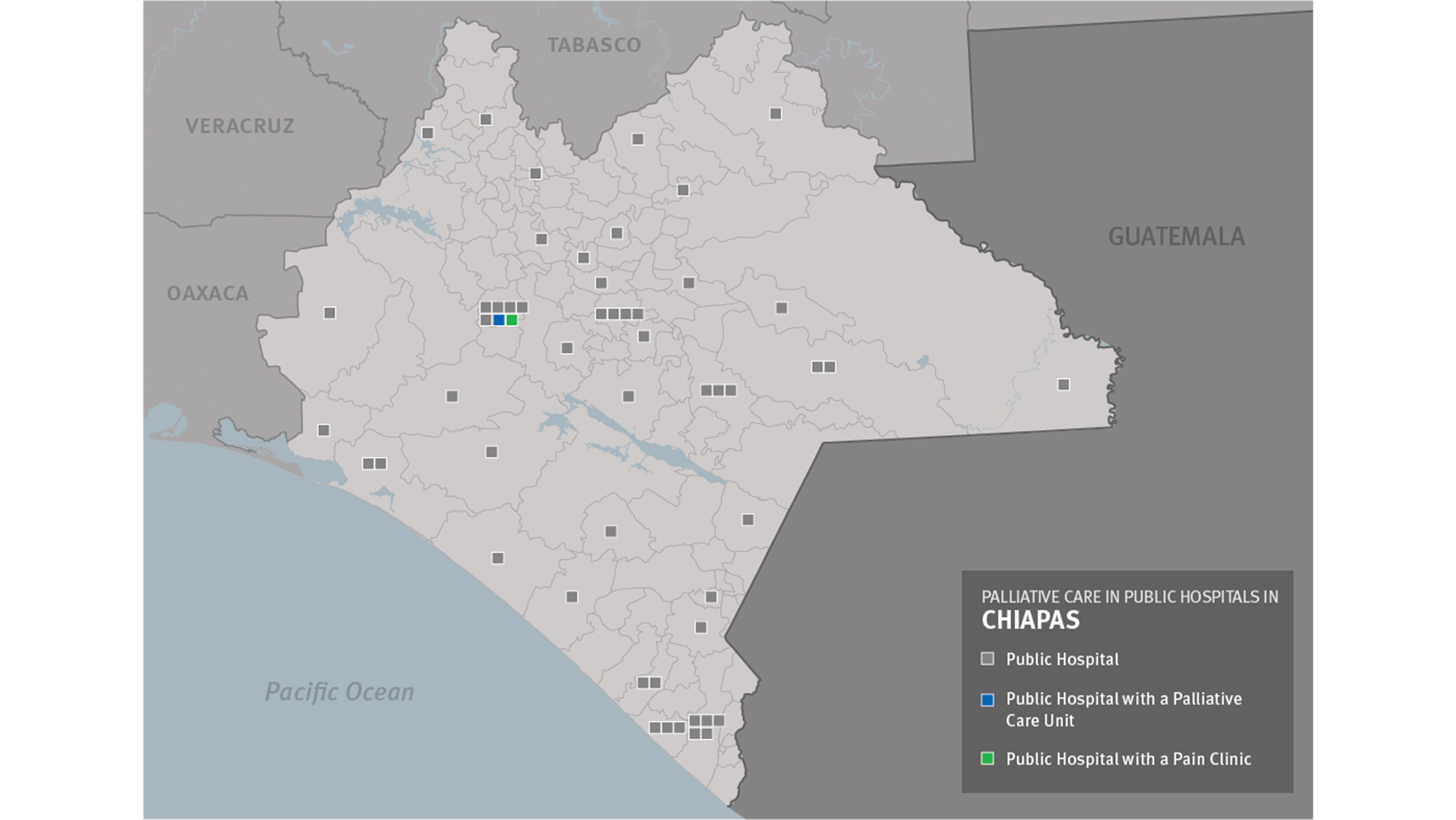

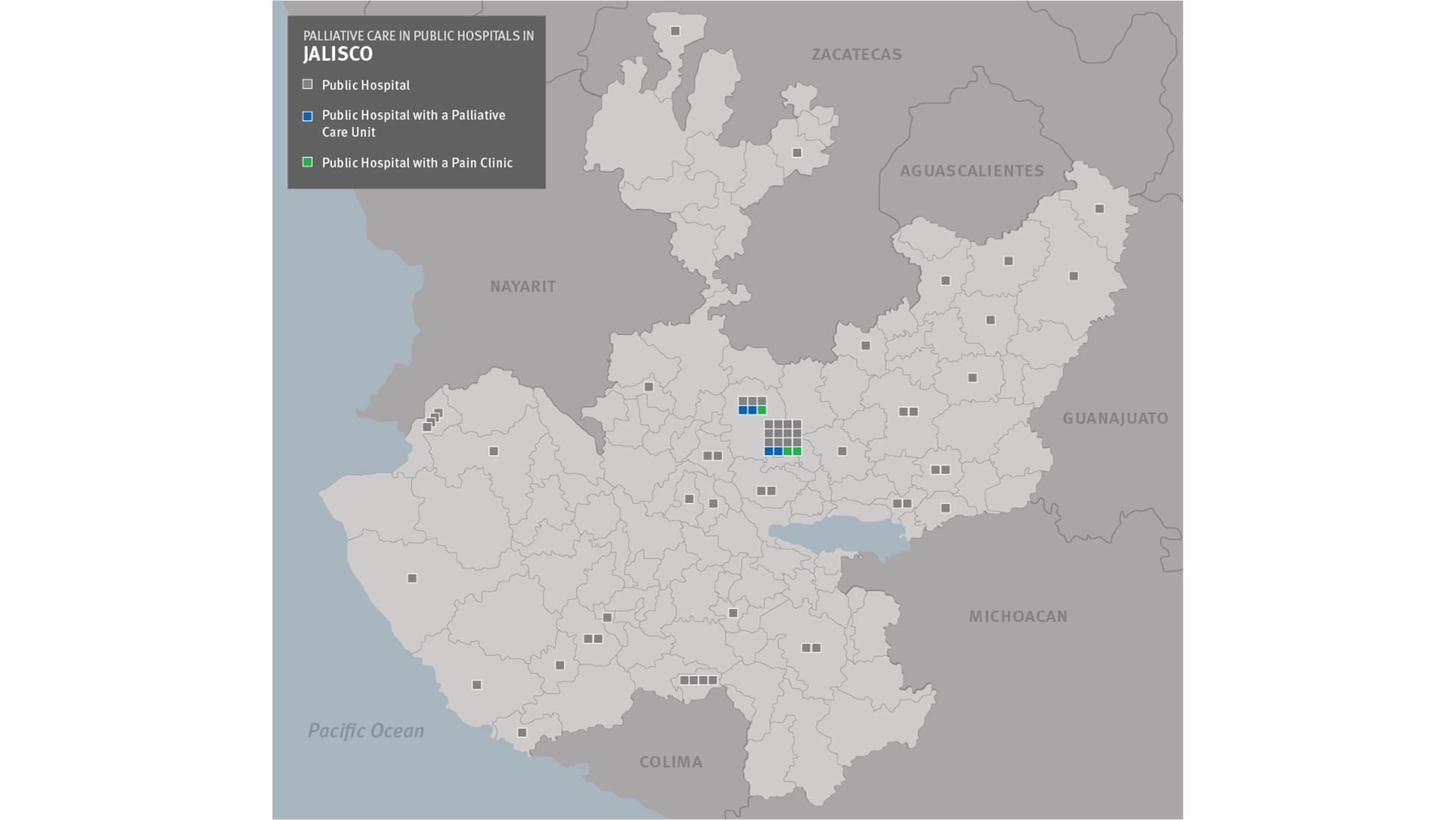

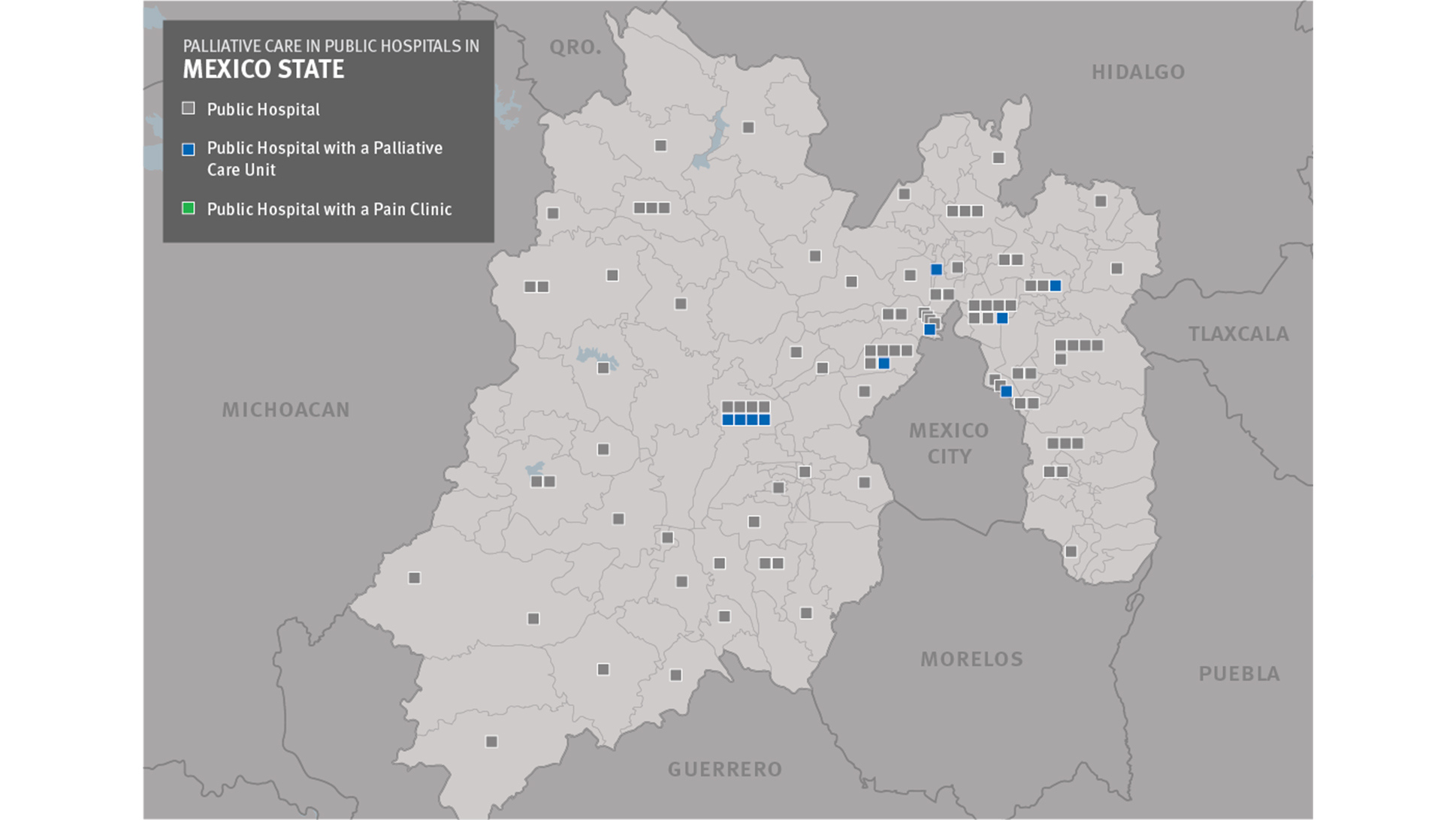

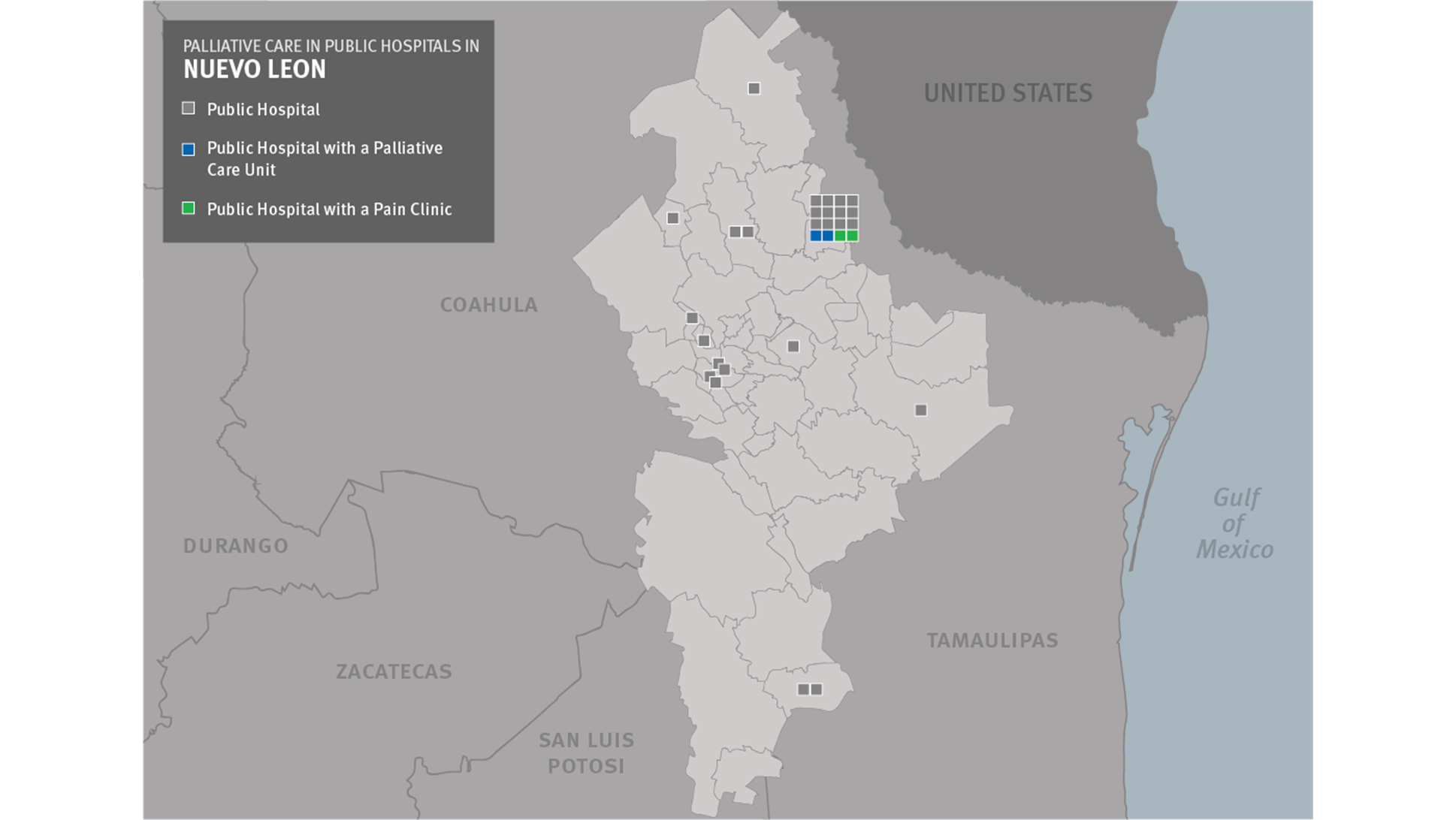

Human Rights Watch estimates that many thousands of people in México have no access to palliative care whatsoever as this service remains unavailable in most parts of the country, especially outside state capitals. A review of two recent studies of palliative care services and pain clinics, presented in Appendix 1, shows that seven of México’s thirty-two states—Coahuila, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Quintana Roo, Sinaloa, Tlaxcala and Zacatecas—with a combined population of almost 16 million people do not have any known palliative care services in the public healthcare system; one of those states, Tlaxcala, does not have any hospitals with a pain clinic either.[36] Another seventeen states have just one palliative care service, in each case in the capital city. Just five of México’s states—Guanajuato, México State, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz—have palliative care services and/or pain clinics available in multiple cities. The overview map shows the distribution of palliative care services and pain clinics around the country.

Only in México City do palliative care services exist in at least one hospital of each of México’s three largest insurers, IMSS, ISSSTE, and Seguro Popular. Durango, Guanajuato and Jalisco are the only three states in which there are hospitals associated with these three insurers that have a palliative care service and/or pain clinic. Ten other states have a palliative care service or pain clinic in hospitals associated with two of these three insurance providers. As México’s health insurers do not cross honor each other’s policies, even in states where palliative care is available in some hospitals, many people who need it may still not have access because they do not have the right insurance.

As the overview map shows, the situation is particularly dire for people who live outside of state capitals. In both Chiapas and Jalisco, two of México’s larger states, there are dozens of large and midsized towns that do not have any palliative care services or pain clinics. Our research found that in Chiapas, Jalisco and Nuevo León, palliative care was almost exclusively concentrated in capital cities (see Table 1). The state maps, see Section entitled “Accessing Strong Pain Medicines”, demonstrate visually how far people in communities all over these states must travel to access palliative care and pain treatment. By contrast, in México State, where there are palliative care units in hospitals in seven different cities, the distances are significantly smaller.

|

State |

Hospitals in public healthcare system[37] |

Number with palliative care service and/or pain clinic |

Number with pain clinic but no palliative care unit |

|

Chiapas |

59 |

1 |

1 |

|

Tuxtla Gutiérrez |

7 |

1 |

1 |

|

Rest of state |

52 |

0 |

0 |

|

Jalisco |

69 |

4 |

3 |

|

Guadalajara |

22 |

4 |

3 |

|

Rest of state |

47 |

0 |

0 |

|

México State |

114 |

10 |

0 |

|

Toluca |

17 |

4 |

0 |

|

Rest of state |

97 |

6 |

0 |

|

Nuevo León |

32 |

2 |

4 |

|

Monterrey |

16 |

2 |

2 |

|

Rest of state |

16 |

0 |

2 |

Ximena Pérez was a 57-year-old mother and grandmother who lived with several of her children, grandchildren, and some animals in a home just outside of San Cristóbal de las Casas, a city in Chiapas.[38] She worked in a bakery until she became ill in 2012. Pain in the right side of the stomach was the first sign that something was wrong. Pérez initially thought she had a bout of gastritis, but when the pain did not subside she decided to seek medical help. A local doctor examined her and discovered that she had a significantly enlarged gallbladder. A subsequent tomography found a tumor in her liver.

The physician referred Pérez to a surgeon at a local general hospital to see whether the tumor could be removed. Her family scheduled an appointment. By the time of the appointment, Pérez’s pain had become very severe. She told a Human Rights Watch researcher: “[It was there] the whole day, the whole day…In truth, I could not bear it anymore.” She added that she could no longer sleep for more than about a half hour at a time.

When Pérez got to the hospital, an unpleasant surprise awaited her. The surgeon was not there so the appointment had to be rescheduled a full month later. Pérez told the hospital staff that she was in severe pain but only received pain medicines that are routinely sold over-the-counter in pharmacies and are not recommended for use for more than a few days because of its side effects. Pérez’s daughter said:

My mom came [to the hospital] in a lot of pain but they didn’t pay attention…They only gave her ketorolac but that did not control the pain…I asked the doctor what my mom had…We were told to wait for the appointment with the oncologist…The appointment was canceled and another was scheduled for a month later…But my mother spent a lot of time in pain.

Pérez herself said that “when I left [the hospital] I left crying because it hurt [so much].”

The family learned about a pain clinic in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the capital of Chiapas, but Pérez’s state of health was too bad for her to be able to make a trip that would take almost a full day. Family members told a Human Rights Watch researcher that they were at a loss as to what to do.

A few weeks before our interview, a neighbor told the family about a primary care physician in San Cristóbal who was specializing in pain and palliative care. The family made an appointment with the doctor who examined her and prescribed opioid pain medicines. Pérez told Human Rights Watch: “I thank God for this doctor because with this [medicine] I can tolerate it.”

Dozens of the patients we interviewed had managed to access palliative care at the time of the interview but said that they had faced significant delays—often months—in getting this care. In most of these cases, the hospitals where they sought care did not offer palliative care but did not refer them to providers that did. As a result, they struggled with symptoms that were inadequately controlled until they eventually found a palliative care provider on their own.

These people often described increasingly desperate searches for better care options and eventually, frequently through word-of-mouth and often very late in the illness, ended up with a palliative care program. For example, Guadalupe Herrera who has advanced diabetes described having significant neuropathic pain for over a year. She said that she has trouble putting on shoes because of a burning sensation in her feet: “It is as if someone is putting needles in my feet.” She told a Human Rights Watch researcher:

I went back to the local clinic when weak pain medicines did not work. They told me the burning is because of diabetes. It's like they told me I would have to live like this [with the pain], that there was no remedy…The pain makes me feel depressed. My state of mind is much affected by the pain. I'm a big cry baby but sometimes it hurts so much.[39]

There are manifold reasons for these kinds of delays in the provision of palliative care: physicians may feel that they are able to provide adequate care themselves despite not having any training in palliative care; they may be reluctant to refer patients to other departments at their hospital or to other institutions; the absence of referral protocols and information about hospitals that have palliative care complicates referrals as do the lack of cross-honoring of health insurance and the absence of any palliative care services at any nearby hospital.

The situation at a specialized pain and palliative care institution in the Zapopan area of Guadalajara offers a particularly vivid example of how the lack of a referral system and late referrals lead to unnecessary suffering. Instituto Jalisciense de Alivio al Dolor y Cuidados Paliativos (Instituto Palia) is an institution of the Jalisco state government that offers pain management and palliative care to patients irrespective of their insurance status. It has several multidisciplinary teams that visit patients in the metropolitan area of Guadalajara in their homes to provide them palliative care. It is a unique institution in México that offers a service—full-fledged home-based care by a team consisting of a physician, nurse, social worker and psychologist—that few other institutions in the country can match.

Yet, according to Instituto Palia’s staff, fewer than 50 percent of its patients come via referral by doctors at other institutions. While the institute does not collect data on referral sources, all physicians at the institution we interviewed lamented the fact that so few doctors at other hospitals referred patients directly to them—or did so very late—despite not having the capacity to care for the patients properly themselves. Dr. Rosa Margarita Álvarez, one of those physicians, commented: “The majority of our patients are referred by other patients or someone else [not doctors]. Eighty percent come with pain that has not been treated properly.”[40] Dr. Karla Madrigal, another physician at the institute, told Human Rights Watch:

Very frequently patients are referred late. Often, people come to us on their death bed. When you go [to their homes] the next day the patient is already dead. They are sent at the very end…They [the relatives] are desperate, someone tells them about us... [41]

When we interviewed María García, a woman of around 70, she lived in a modest home in San Juan de los Lagos, a small town in Jalisco, with her husband, youngest daughter and baby grandchild.[42] She had been completely bedridden for two years as the result of a metastatic tumor in her back that had left her paralyzed.

She had become ill a few years earlier when she developed pain in her leg, which later extended to her spine. She tolerated the pain for some time but eventually went to the doctor who discovered tumors in her back and leg. García underwent surgery to amputate part of one leg and remove the tumor in her back. The operation caused damage to the nerves in her spinal cord, which left her unable to walk.

García had a series of health needs, ranging from increasingly severe pain to skin care—people who are bedridden often develop bed sores—to psychosocial care. While María had insurance through Seguro Popular, the local hospital in San Juan de los Lagos did not offer palliative care. Her doctor prescribed analgesics but they were not strong enough to control her pain. García needed morphine or another opioid pain medicine but San Juan de los Lagos did not have physicians who prescribe these or pharmacies that sell them. García told Human Rights Watch researchers that her pain was very severe. She said:

I almost faint. I feel like it’s going to give me a heart attack…It’s like electrical charges from where I have the prosthesis. I have shocks that go up and down. I scream, I cry. I don’t know what I do.

Unable to get proper care locally, García’s family took her to Aguascalientes and Guadalajara, a difficult one-and-a-half hour journey for a woman who is paralyzed and in severe pain. A hospital in Guadalajara provided García with a morphine infusion pump that helped her control her pain.

By the time we interviewed her, however, García was no longer able to travel to Guadalajara for check-ups. Her aging husband had to travel once a month to the hospital there in order to buy a new supply of morphine, which is not covered under Seguro Popular. The palliative care team at the hospital in Guadalajara had to manage García long distance and make adjustments to her treatment without being able to examine her.

We encountered this scenario repeatedly in our interviews, of people with terminal illnesses—and often in rapidly deteriorating condition—traveling long distances, sometimes as long as six to eight hours on a bus, in order to receive palliative care or receiving it remotely. With no hospital close to home offering palliative care—or no system to refer patients to hospitals that do—these people faced the unenviable choice between traveling long distances, often on rickety buses, in order to access palliative care or asking relatives to do the traveling for prescriptions and receiving suboptimal care.

This scenario is very common for the simple reason that diagnosis and curative treatment for life-limiting illnesses is often available only at tertiary care institutions. As primary care physicians do not have the equipment or knowledge to treat cancer or heart disease, for example, they generally refer patients to secondary care institutions as soon as they suspect a serious condition. In many cases, that process repeats itself at the secondary care level and patients are referred to a specialist hospital. With each referral the distance patients must travel to access treatment increases, as specialized hospitals tend to be located only in major metropolitan areas.

For curative care, the cost and inconvenience of such travel may be unavoidable as primary and many secondary care facilities do not have the specialists, diagnostic equipment, laboratory capacity, and treatment options available to properly manage patients with complex illnesses. This is not true, however, for palliative care, which for most patients does not require any complex interventions and can be provided at lower levels of care. Moreover, as we have seen in several of the testimonies above, for people with terminal illness travel is extremely difficult, making it all the more important that palliative care be available close to or in the home.

When people who are terminally ill can only access palliative care by travelling long distances to tertiary care hospitals the central objective of this care—safeguarding the dignity of these people—is not achieved. Mexican legislators were clearly mindful of that fact when they adopted the amendments to the health law and explicitly included a right to receive palliative care in the home. Yet, palliative care services have not been decentralized sufficiently to allow people to receive it in or close to their homes.

We encountered this scenario over and over again when at México’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) in México City. We interviewed multiple patients who were in their last weeks of life and arrived at the hospital in a terrible state after traveling for hours on buses. In some cases, relatives carried their loved ones wrapped in blankets from the bus or taxi to the hospital because the patient could no longer walk or stand. We also interviewed numerous relatives of patients who were no longer able to make the trip to the NCI. In such cases, the palliative care team had to adjust treatment decisions based on descriptions by relatives rather than on examination of the patient. Often, the care offered was reduced to just renewing prescriptions. Better than being left without care but far from the quality of care patients should receive.

In 2012, the palliative care service at the NCI conducted a review of the cases of 600 incurable cancer patients attended in 2010, many of whom had lived outside México City. The review found that almost 30 percent of patients attended the service only once, even though all were given a follow-up appointment.[43] While the study did not establish the reasons why patients did not return, the NCI’s doctors believed that a significant proportion were unable to return because they were too ill to travel or lacked the financial resources to do so.[44]

“[I have a pain all the time but] when food goes into my colon I cannot tolerate the pain. It is like a bomb…In the hospital, I was told to endure the pain.” – Liliana Arroyo, a patient with colon cancer[45]

Pain treatment is a critical component of palliative care and our research specifically examined the availability and accessibility of strong analgesic medicines. Although strong analgesic medicines like morphine are relatively inexpensive, we found that these medicines are often difficult to access because few physicians are trained in using them and because they are controlled substances and thus subject to special regulations.

The experiences of people we interviewed point to a gaping divide between the availability of pain medicines for people who live in major metropolitan areas or state capitals and those who live in smaller towns and rural areas. For the latter, accessing opioid analgesics is enormously difficult because very few doctors outside of state capitals seek licenses to prescribe them and almost no pharmacies sell these medicines. People in state capitals generally had better access to doctors able to prescribe these medicines but frequently encountered difficulties filling prescriptions because of strict rules and shortages of medicines.

The government has announced steps to try to resolve many of the problems our research identified. For discussion, see Chapter V.

There is an alarming lack of doctors who obtain licenses to prescribe opioid analgesics and pharmacies that dispense them in much of México. While in major cities, such as state capitals, there generally are some doctors with such licenses in pain clinics or palliative care units at major hospitals, outside the major cities it is often impossible to find doctors licensed to prescribe these medicines or pharmacies that dispense them. Patients who live there face the unenviable choice between traveling long distances to access treatment—often while in pain—or suffering without it. The reasons for the shortage of prescribers of these medicines, which are related to insufficient training of physicians in pain management and complicated bureaucratic requirements to be able to prescribe, are described in Chapter III.

As part of our research in the states of Chiapas, Jalisco, and Nuevo León we sought to identify all physicians who prescribe opioid analgesics to patients with chronic pain and all pharmacies that dispense these medicines. While there are multiple prescribers and pharmacies in the capital cities of all three states, there are almost none in the rest of these states. In Jalisco, for example, there are 14 municipalities with populations over 50,000 people. Just three of them have physicians who prescribe opioid analgesics for chronic pain and only one—Puerto Vallarta—also has a pharmacy that sells them. In Chiapas, two of the 22 municipalities with populations over 50,000 people outside of Tuxtla Gutiérrez—San Cristóbal de las Casas and Tapachula—have physicians that prescribe these medicines but only Tapachula has a pharmacy that sells them. None of Nuevo León’s three municipalities of more than 50,000 people outside the metropolitan area of Monterrey have physicians that prescribe opioids for chronic pain or pharmacies that sell the medicines. The state maps offer a visual representation of the situation in these states.

A publication by Raymundo Escutia, a pharmacist in Guadalajara, shows a similar dynamic in other states. His research found that in 2011 three states did not have a single pharmacy that sold oral morphine; in another 16 states, there were no such pharmacies outside the state capital.[46]

As a result, people with pain from outside the major metropolitan areas often have to travel all the way to their state capitals in order to obtain or fill prescriptions for strong pain medicines. For many, such travel is an insurmountable barrier as they or their families either do not have the ability—financially or physically—to travel long distances or because their physicians do not refer them to colleagues able to prescribe opioid analgesics.

Dr. Araceli García Pérez, the only physician in Ciudad Guzman, Jalisco, who prescribes opioid analgesics for chronic pain, described the challenges for her patients as follows:

[Most of my] patients are unfortunately of low resources. Many have never been to Guadalajara. [It is a challenge for them] to find the Farmacias Especializadas where [morphine] is sold...Those with money…drive over to buy the medications but most patients have little means and a limited cultural level. For poor patients [it means] spending more money on the trip, without knowing Guadalajara...So it becomes something impossible for them to do.[47]

She noted that these patients will pay more to travel to Guadalajara than for the medications.

Dr. Juan José Lastra, a general practitioner licensed to prescribe opioid analgesics, has a practice in Ajijic, a community outside Guadalajara with a large number of retired foreigners, mostly from the United States and Canada. He said:

If you tell the patient or the family: “Here’s the prescription, go and buy it,” the patient is going say that he needs it right now. They say: “It’s going to take me 1 hour to get to Guadalajara, half an hour in traffic, then back – it’s going to take me three hours.”[48]

Dr. Carlos García, also a general practitioner in Ajijic said: “The majority of my patients are old. They mostly have serious health conditions, such as cancer. The patient generally can’t go so a family member has to make the trip.”[49]

The lack of physicians that get licensed to prescribe opioid analgesics and the lack of pharmacies that sell them create a vicious cycle that perpetuates this untenable situation. Medical doctors do not prescribe opioid analgesics because of the hassle of obtaining prescription rights. Pharmacies do not stock the medicines because there are no physicians who prescribe them. This, in turn, becomes an additional disincentive for doctors to obtain prescription rights: Why should they do all the work to be able to prescribe these medicines when patients cannot fill the prescriptions locally anyway?

While the situation in state capitals is significantly better than outside, there is a shortage of physicians licensed to prescribe opioid analgesics and pharmacies that sell them even there. In many places, only doctors at pain clinics at tertiary level hospitals have prescription rights, meaning people can only get these medicines if they are referred to those clinics. Furthermore, even in state capitals, the numbers of pharmacies that sell opioid analgesics is very low. In the metropolitan area of Guadalajara, a city of about five million people, just fifteen pharmacies stock these medicines.[50] In Tuxtla Gutiérrez, a city with a population of half a million people, just three pharmacies stock them.

This means that patients often have to travel significant distances within these cities in order to get to the doctors’ offices that prescribe these medicines and to pharmacies that can fill prescriptions. Sofía González, for example, a chronic pain patient in Guadalajara, told a Human Rights Watch researcher: “I have to go to a pharmacy that has controlled medicines...None of these pharmacies are nearby. I usually leave in the morning and have to take two buses. It takes two or three hours. Sometimes I can't fill the prescription. I call and they tell me whether they have it. Sometimes they don't...I try to talk to them before [my medicines] finish. When I have few drops left, I talk [to them]. I don't want to end up without...”[51]

Even when people are able to obtain a prescription for an opioid analgesic and access a pharmacy that sells these medicines, they may still face challenges getting their medicines: México’s inflexible regulations for prescriptions of opioid analgesics and unreliable supply often lead to pharmacies being unable to fill prescriptions for these medicines. Some doctors we interviewed estimated that pharmacies cannot fill up to 15 percent of their prescriptions for opioid analgesics (see below, Chapter III) because of current prescribing rules. For patients, the result can be being left without adequate pain medicines and spending hours traveling back to the doctor and then returning to the pharmacy.

For example, José Luis Ramírez, a man with a large throat tumor from Guadalajara, told a Human Rights Watch researcher that he had to return to the hospital when the pharmacy did not have the name of the medication indicated in the prescription, even though the same medication from a different pharmaceutical company was available:

There is one that is called Analfin [morphine] and they [only] have it with a different name. And because of that they don’t give it to you. You have to go back to Palia [the hospital] so that they put it [the right name]. Otherwise they can’t sell it to you.[52]

A one-way trip to the hospital takes Ramírez an hour-and-a-half on public transport.

The brother of Esmeralda Márquez, an 82-year-old patient with chronic pain, said that on various occasions pharmacies could not fill prescriptions:

If you have a prescription for 15mg but they don't have them, they can't sell [other strengths]. I have to talk to the doctor and return to Palia [the hospital] to get a new prescription. It’s controlled [strictly]. I told her [my sister]: You know, it would be easier to buy marijuana.[53]

Describing her desperation when her relatives were unable to fill her prescription, Daniela Moreno, a chronic pain patient in her eighties, said:

The day I don’t have the tablet, I feel desperate…I feel in the night, oh, I can’t sleep. The eight days that they couldn’t find it…one day I put water in the bottle that had contained the tablets [and drank it] to see if it would stop the pain…It was desperation.[54]

Throughout our research, both primary care physicians and oncologists interviewed repeatedly told us that they do not prescribe opioids because they see it as a pain specialist’s job. These doctors often said they either prescribe weak pain medicines, sometimes even when pain is moderate to severe, or refer patients to a pain clinic.

Testimony from an oncologist who works in Tuxtla Gutiérrez and Tapachula in Chiapas was typical. The oncologist said that he had never sought a license to prescribe opioid analgesics even though he said it would not be hard to get. He said that he sends private patients to a palliative care expert in Tuxtla Gutiérrez and patients with pain at his public hospital in Tapachula to the pain clinic. The oncologist said that even though he routinely has patients with moderate to severe pain he does not have the “profile” to prescribe opioids and that he “prefers that they are managed by an expert.”[55]

Dr. Araceli García Pérez from Ciudad Guzman, the only physician licensed to prescribe opioid analgesics in her city of about 100,000 people, said:

Normally patients have to go to a pain doctor because general practitioners are not trained for this kind of situation. They therefore prefer not to get involved in this stuff. It is a pain having to ask for prescription forms etcetera when you don’t really know how to manage these things [prescribing of opioids].[56]

For patients, however, this often means adding extra steps, requesting additional appointments with the pain clinic and making extra trips to the hospital. It also appears to result in the overprescribing of weak pain medicines by physicians who do not prescribe opioids but delay referring their patients to pain or palliative care specialists. A number of palliative care or pain physicians complained that their colleagues’ lack of knowledge about pain management led to the excessive use of over-the-counter pain medicines which, when used over extended periods of time, can do serious and irreversible damage to the gastrointestinal tract and the kidneys. Dr. Jesús Medina, a physician at Instituto Palia, described a situation he and his colleagues commonly see:

Patients come in very advanced stages. They've been on non-opioids pain medicines for years. The doctors have already screwed up their stomachs. They already have renal problems due to high use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)…The NSAIDs are much more dangerous than the opioids. Side effects of narcotics can be managed. We have geriatric patients who have been using NSAIDs daily for 11 to 14 months. Of course they already have intense gastrointestinal problems. They are nutritionally compromised as they are not eating because it hurts to eat.[57]

Dr. Araceli García Pérez from Ciudad Guzman concurred:

Sometimes surgeons, gynecologists, oncologists have patients who are terminal that should be in palliative care…Oncologists don't know how to treat patients with pain. I’ve seen patients [in moderate to severe pain] that they [the oncologists] continue to give paracetamol, paracetamol and paracetamol. I tell them why? They say it's the only thing. The patients are already almost in death throes…and they still continue to give them paracetamol. They [the doctors] panic at the thought of morphine.[58]

A patient who was receiving 50 mg of morphine per day told us that her oncologist recommended that she immediately stop taking morphine after she had a colectomy.[59] The oncologist apparently did not realize that this would have caused her patient to go into withdrawal. Luckily for the patient, she consulted her doctor at Instituto Palia before following the oncologist’s recommendation. Dr. Jesús Medina, the physician who treated her at Instituto Palia, told Human Rights Watch he encounters stories like that on a regular basis.[60]

Antonio Méndez, the youngest child in a middle-class family in Tepatitlán de Morelos, a town of about 100,000 inhabitants in the state of Jalisco, was almost six when his parents noticed that he had a significantly swollen ganglion in his neck in 2008.[61] Thinking it was an ordinary infection, a local doctor prescribed antibiotics. However, neither this nor a second course of antibiotics succeeded in bringing down the swelling. Although Antonio was eating well, his parents said that he also inexplicably began to lose weight. Concerned about his health, they took him to a hospital in Guadalajara for a biopsy. The results came back positive for a rare form of cancer called rhabdomyosarcoma, a malignant tumor of the muscles.

When Human Rights Watch researchers visited him in February 2012, Antonio was nine and had been receiving chemo and radiation therapy for three-and-a-half years at a hospital in Guadalajara, about 50 miles from his home. His prognosis was bleak: he had metastases in his head and in his lungs. At the time, Antonio had a visible tumor in his neck and his eye had recently become swollen as well. We decided not to interview him because he was experiencing significant discomfort, but we spoke to his parents.

Antonio’s parents knew that their son’s cancer had become incurable and they were ready to accept the fact that he was going to die. They had grown increasingly wary about continuing with chemotherapy and the impact its side effects had on Antonio. As his mother told us:

Antonio has been getting chemo for three years. [He had] only a single three month [break] because he was getting radiation therapy…[T]he consequences of the chemo have been many: hemorrhage, constipation, nausea, throwing up everything, low immune system, low platelet count, meningitis infection...This month, the chemo burnt a little vein here. The chemo has so many consequences…

While the family was ready to embrace treatment focused on Antonio’s quality of life rather than on cure, the hospital did not have a palliative care unit or staff trained in palliative care. None of the doctors at the hospital had discussed the option of palliative care with them despite the fact that Antonio was a likely candidate for palliation and that Guadalajara, where he was receiving treatment, has multiple hospitals that offer palliative care, including for children. Instead of offering palliative care, Antonio’s oncologist convinced his parents to continue with more chemotherapy. Antonio’s mother told us:

When I was told a year ago that the cancer had infiltrated, I said: “We’re not going to give him any more chemo.” But the doctor said: “If you don’t give him chemo, it [death] is going to happen sooner.”

Given no other option, Antonio’s parents agreed to continue with chemotherapy despite their misgivings.

When we met with them, Antonio’s parents had no idea what palliative care was, even though it coincided almost exactly with the wishes they had for their son’s care. Unfortunately, they said, it was very difficult to discuss their priorities for their son’s care with the oncologist. Although Antonio’s mother thought the doctor was very competent, she was not willing to engage in discussions of their son’s care. His mother said:

Antonio’s oncologist is of few words. She gives you the diagnosis but she never explains anything. Never, ever. And she doesn’t like you asking. If you keep asking, she stops you, kind of “that’s enough.”

Antonio’s father added: “Don’t even ask because she’s very sensitive.”

In December 2011, Antonio developed severe pain. His mother said that he would cry a lot and grab his head. The oncologist referred him to the hospital’s pain clinic where a doctor prescribed morphine. However, the doctor had instructed Antonio’s parents to give him a quarter tablet of morphine in the morning and another in the evening. If he suffered from a lot of pain the doctor told them to give him three or four doses per day. These instructions were inconsistent with recommendations from the WHO on cancer pain treatment, which stipulate that patients should receive morphine every four hours to ensure continuous pain relief.[62] As a result, Antonio continued to be in pain during much of the day. Eventually, his mother decided herself to start giving him morphine every four hours when he was in a lot of pain.

The doctors at the pain clinic also failed to provide Antonio’s parents with adequate information on the side effects of morphine. His mother said that they “have never really talked to me about it or anything.” As a result, Antonio suffered from constipation and nausea without appropriate treatment. She said:

When I gave it [morphine] to him for the first time…his stomach would hurt 20 minutes later. What is the point on of taking pain away from him if we cause another [symptom]…?” We had to go all the way [to Guadalajara] to ask.

Antonio’s mother also said she was concerned—unnecessarily—that if her son received morphine now it might stop working when his pain would get even worse: “I told myself: ‘Well, I’ll give it to him more often,’ but at the same time I thought: ‘If I give it to him more often, when he experiences this strong pain it’s not going to work on him.’”

Their son’s illness had created enormous stress and anxiety within the family, something that a palliative care team could have helped resolve. Antonio’s mother, for example, described a near breakdown she had suffered a week before our visit in February 2012:

Last week I felt so bad when I saw Antonio’s eye [swollen] like that. I have lived through the disease with Antonio for three years…and he has been severely ill... Still, [it was the first time] that I said: “No, it’s my husband’s turn now, I don’t want to see anymore.” And at the same time I said: “What if my son sees that his mother isn’t present anymore,” so then I stayed. But yes, emotionally I was about to quit last week.

Weighing most heavily on Antonio’s parents was the lack of information about what was going to come as their son deteriorated and about how they should care for him. They were in charge of caring for a child who was dying and nobody had told them or him what to expect and how to manage. When Human Rights Watch staff offered to put the family in touch with a pediatrician in Guadalajara who was specialized in pediatric palliative care, one of Antonio’s mother’s first questions was: “His oncologist, she hasn’t talked to me honestly about what can happen. Can she [the palliative care physician] talk to me openly about that?”

The pediatric palliative care physician, Dr. Yuriko Nakashima, cared for Antonio during his last few months, controlling his pain and other symptoms and assisting him and his parents between home visits by phone and video. Antonio eventually died peacefully in May 2012.

The WHO defines children’s palliative care as “the active total care of the child’s body, mind and spirit,” as well as support for the family.[63] Children’s palliative care includes efforts to assess and treat pain; the provision of medicines in appropriate formulations for children; support for the child through play, education, counseling and other methods; child-appropriate communication about the illness; and communication with, and support for, the family.[64] It should also address child protection, as some severely ill children are vulnerable to exploitation, abuse and neglect.[65] Hence, palliative care for children requires pediatric expertise, including on child-specific symptoms and diseases, as well as expertise in child psychology and child protection.

Palliative care is very important for children with life-limiting illness. For children, serious illness, pain, hospitalization, and invasive medical procedures are often profoundly disorienting and traumatizing and can cause great suffering. For parents and caregivers, watching a child suffer from symptoms and medical procedures, balancing the needs of the sick child with those of other children, and facing the prospect of potentially the child’s death, cause great distress. Pediatric palliative care can help both children and parents navigate these difficult circumstances by relieving distressing physical symptoms, minimizing pain due to medical procedures, and enhancing communication among health care workers, children and parents about the child’s illness and prognosis.

Thousands of children in México need palliative care annually, including more than 1500 children who die of cancer each year. Doctors at the palliative care unit of the National Pediatrics Institute (NPI) in México City, the largest children’s hospital in the country, estimate that about 40 percent of all children attended at this tertiary care hospital have life-limiting illnesses and potentially require palliative care.[66] A study of more than a thousand children attended by the palliative care unit of the NPI found that about 38 percent of patients had cancer; almost 30 percent had severe neurological conditions, such as epilepsy, encephalopathy, and hydrocephaly; and the rest a variety of other conditions.[67] A review of symptoms of a sample of these patients showed that 70 percent suffered from bronchial or oropharyngeal secretions (wet secretions from the mouth or throat that cause an unpleasant rattling sound) and 67 percent suffered from pain.[68]

As with adults, very few hospitals offer pediatric palliative care, meaning that this health service is inaccessible to many families who require it. Children are even worse off as only six hospitals in all of México—the National Pediatric Institute, Hospital General Dr. Manuel Gea González in México City, the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, Hospital del Niño in Toluca, Hospital del Niño in Morelos and Hospital Infantil Teletón de Oncología, a charitable hospital—are known to have specialized pediatric palliative care teams. The remainder of the more than forty hospitals in México that attend to children with cancer and other advanced diseases do not have known palliative care services.

The pediatric specialty hospital in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Hospital de Especialidades Pediátricas, is one example. This hospital, which opened in 2006, offers comprehensive secondary level health services for children in Chiapas, including treatment for cancer and other life-limiting illnesses. It is the only such hospital in the state. The hospital’s oncology department sees about 60 children with cancer per year.[69] According to oncologists at the hospital, only about 20 percent of these children survive.[70]

Yet, the hospital does not have a palliative care unit, anyone on staff with palliative care training, or any physician licensed to prescribe strong opioid medicines for chronic pain. Children who become incurable are sent home and told to come back every two weeks for follow-up appointments. Patients who require pain management are sent to the regional hospital, which has a pain clinic but no staff trained specifically in pediatric pain management. The hospital has no call service to support parents of children who are dying at home. When a child has complications or a spike in pain they have no other option but to go to the emergency room of the hospital. For many patients, however, this trip can take many hours.

Oncologists at the hospital lamented not being able to offer palliative care. One told Human Rights Watch:

I think palliative care is very important because many patients feel that you are not going to attend to their needs anymore, that you are abandoning them. If we had palliative medicines, we could continue to have support of the hospital.[71]

The experiences of two public children’s hospitals in central México we visited demonstrate how a relatively limited investment in palliative care, paired with strong leadership, can achieve significant results in improving the care for children with incurable or terminal illness. The two hospitals—the Hospital del Niño in Toluca, México State and the Hospital del Niño in Cuernavaca, Morelos—each set up palliative care programs in 2013.[72]

Both hospitals use broadly similar models to provide palliative care. Each has at least one full-time staff member dedicated exclusively to palliative care that coordinates the care of patients. Both hospitals have home-based care services and offer round-the-clock support to patients and parents via telephone and/or text message. The administrations of both hospitals have also designated physical space—in Cuernavaca, a procedure room, in Toluca, a small office—to the palliative care service.

In both hospitals, the decision to refer a child to palliative care is taken by the treating physician, usually when curative treatment is discontinued. Following such referral, the physician works with the multidisciplinary palliative care team to develop a care plan for the patient; a meeting is held with the family to discuss the child’s prognosis and the options for care; the family is trained in the provision of basic care at home and provided emergency contact information for the palliative care services; and ultimately, in most cases, the child goes home where he or she receives regular visits from members of the palliative care team.

In Toluca, by June 2014, the palliative care service had cared for 138 children with terminal or incurable illnesses since it began operating in February 2013. At the time of the visit, 59 of these patients had passed away, more than half in their homes. In its first year, the palliative care service in Cuernavaca had cared for 58 children. Three quarters of the forty-five who had passed away did so in their homes.

The directors and staff at both hospitals said that feedback from patients and their families on the palliative care service had been very positive. Furthermore, they also noted that hospital stays for these children were often shorter than before, potentially leading to cost savings for the hospital. They said this was particularly true for children who require round-the-clock ventilators due to severe neurological or congenital malformations. Previously, many of these children had no option but to stay in the hospital for extended periods of time whereas the palliative care services have allowed many of them to obtain these services at home.

Both hospitals also reported challenges. The palliative care teams said that in the beginning, they had encountered significant resistance on the part of some physicians who did not want to refer their child patients to palliative care. They said that over time they had overcome much of this reluctance through training and direct experiences. Many physicians now recognize the benefits of palliative care for their young patients. However, the hospitals cited lack of adequate staff and insurance coverage for palliative care and difficulties prescribing opioid medicines as challenges.