Faith learned she was HIV positive two years ago, after giving birth to her daughter. The Zambian government prides itself on its HIV prevention outreach, and every pregnant woman is supposed to be tested for the virus, to prevent passing it on to their babies. But Faith, now 25, is deaf, and was never tested before the baby was born. Nor did she receive even basic information about HIV.

If people who are deaf don't bring their own sign language interpreter to health clinics, they are unlikely to get information. Even when they do, they are often greeted with stares by other patients and negative attitudes from some health workers. Now, Faith is on HIV treatment, but it’s a struggle. Her 2-year old daughter is positive too, which might have been prevented if Faith had been tested before the baby arrived.

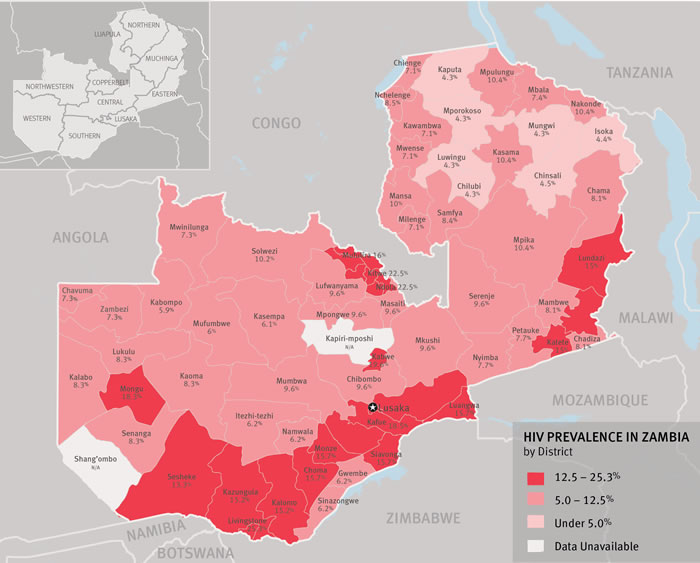

An estimated two million people with disabilities in Zambia face significant barriers to HIV prevention, testing, and treatment, according to a new Human Rights Watch report, “We Are Also Dying of AIDS.” Zambia is a regional leader in providing HIV services.

Yet because people with disabilities in Zambia are often seen as not engaging in sex, they are often excluded from community gatherings where government workers or nongovernmental organizations hand out condoms or educate people about the virus. Children with disabilities are less likely to attend school, where HIV is discussed, and many schools don’t offer the information in accessible formats, like large print or braille. Some disabilities, like deafness, are associated with witchcraft, which leads to additional discrimination in their communities.

SOURCE: Zambia HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Projections Report 1985-2010 (Central Statistical office).

And while there are significant barriers to treatment and prevention, people with disabilities in Zambia are more vulnerable than others to contracting HIV because of lower education and literacy levels, greater poverty, and greater risks of physical and sexual abuse.

When Faith first met the Human Rights Watch fellow Rashmi Chopra, she stared ahead with a blank expression, preferring to let her mother answer questions. It was only when someone placed Faith’s daughter in her arms that she smiled. She had so much vibrancy, and she spent so much time hiding it.

When Faith spoke of her husband, she didn’t call him by name, instead referring to “the father of my baby.” Faith’s husband berates and belittles her. He is often away from home, so Faith’s family has stepped in to help her raise the baby. When Faith asked her husband if he’d been tested for HIV, he wouldn't tell her. Yet Faith wants a relationship with her husband, and she wants her community to see that she is in a relationship.

While many women in Zambia have similar problems, women with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to abuse and abandonment since they are often dependent on others for care and support. Men who choose to be with a woman with a disability may also be stigmatized by their community.

When Faith was pregnant, she did not get any pre-natal care so she wasn’t tested for HIV. She doesn’t like going to her local clinic because of the way people look at her when she is signing. “I feel it, people are staring at me and pointing at me,” she said. “I don’t like coming here.” While Faith wants another child, some healthcare workers have told her she should not have any more because she is unable to take care of her child properly because she is deaf. This attitude alone could deter her from seeking necessary medical treatment.