Sanjar Umarov lifted his pants legs and rolled down his socks to show the scars that criss-crossed his ankles. Umarov, a former political prisoner from Uzbekistan, said the scars served as a permanent reminder of his time in the “monkey cage,” a cell that left prisoners exposed to the outdoors. His first time in that cell, the frigid winter almost killed him. He and the other prisoners, wearing only lightweight shirts and pants, rocked back and forth to keep warm and stay alive.

The second time, it was his fellow prisoners who almost did him in. Guards threw him in the cage after Umarov refused to sign a confession saying the United States gave him $20 million to overthrow Uzbekistan’s government. Other prisoners in the cell were ordered to make him sign. They beat him, broke his thumb, and choked him, damaging his vocal chords and leaving him with a permanently gravely voice. Once they had him on the ground, they repeatedly jumped on his ankles, which were shackled in metal cuffs.

Before he was imprisoned on trumped up charges, Umarov was a leading businessman in Uzbekistan, helping found the country’s main telecom network. He had entered politics gradually, quietly supporting a political party that hoped to help poor farmers in the country’s almost feudal cotton sector. But he grew impatient with the slow pace of change and formed his own opposition party.

Within the year, Umarov was arrested and charged with economic crimes he didn’t commit.

This is par for the course for Uzbekistan’s political prisoners. The country has been ruled for 25 years by Islam Karimov, the Communist Party boss under the former Soviet Union. Under his autocratic rule, a wide-array of Uzbek citizens – including journalists, political opposition activists and religious figures – have been imprisoned in terrible conditions, including beatings and torture, a new Human Rights Watch report shows. Uzbek officials have a particularly cruel practice of extending prison sentences shortly before a prisoner expects to be freed, for reasons as ridiculous as “peeling carrots the wrong way” or “failing to lift a heavy object.”

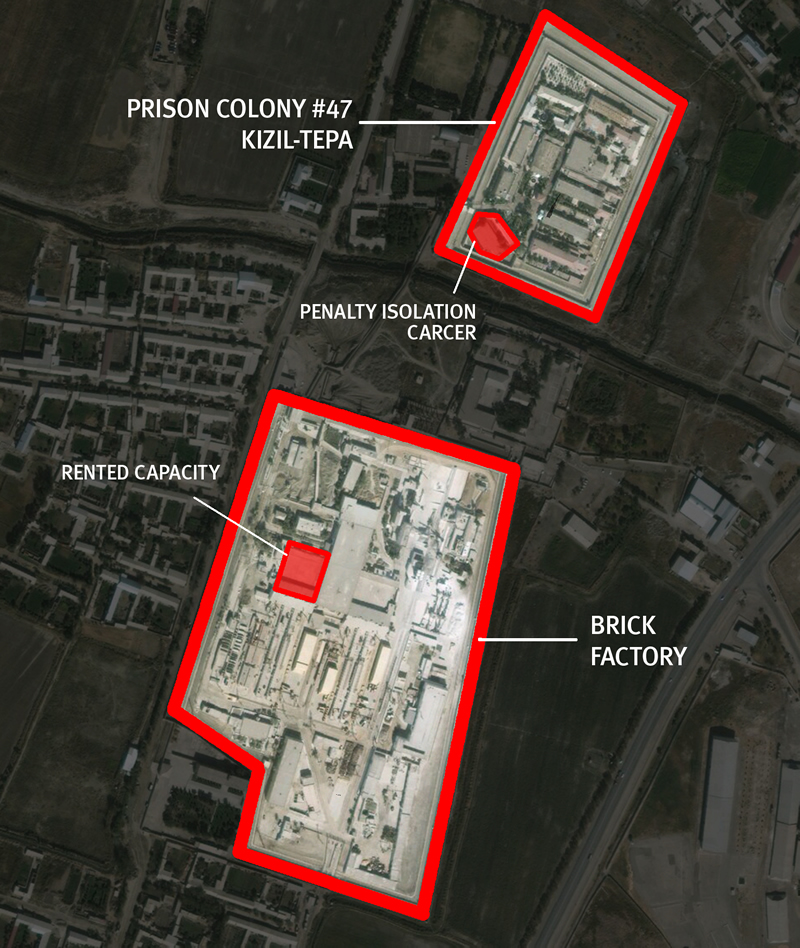

Uzbekistan political prisoners

Umarov in large part credits international pressure for his release from prison. But in general international pressure on Uzbekistan has been sorely lacking. The United States and European Union have consistently appeared reticent to push Uzbekistan to release political prisoners, as the country provides an essential supply route to reach US and NATO troops in Afghanistan. The withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan this year may change this equation, and the world should not keep turning a blind eye to Uzbekistan’s rights abuses.

It’s easy to see why Uzbekistan’s government could fear Umarov’s influence. Even now, with his torture scars and gravelly voice, he speaks with assurance, exuding the charisma and warmth of someone people naturally want to follow. His black hair is fading to gray in the front, and when he smiles or laughs, which is frequently, the tanned skin around his eyes wrinkles pleasantly.

Umarov had studied physics, but when the cold war ended, he saw opportunity in the need to modernize his country. He helped found Uzbekistan’s leading communications company, developed venture capital projects in its energy and transport sectors, and founded an international business school in Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s capital.

When he began dabbling in politics, around 2003, Umarov secretly helped fund the Free Peasant opposition party. Profits from growing cotton dominate Uzbekistan’s economy and fund the government. Farmers are forced to grow cotton and sell it to the government dirt-cheap. Each year the government forces about 2 million people – including doctors, teachers and children – to pick the crop, without pay.

“I wanted to give farmers a voice and power over their land,” he said, describing the poor farmers as little more than slaves.

But Umarov grew frustrated when nothing changed. “I wanted to see something better,” he said. “A moment came when I had to act.” In early 2005, he decided to openly use his influence and formed his own political party, the Sunshine Coalition, which pushed for socio-economic and democratic reform.

That May, a few months later, Uzbek government troops committed one of the worst massacres in the former Soviet Union, opening fire on largely peaceful protesters in the city of Andijan, killing hundreds of men, women, and children as they tried to flee. The government tried to hide the enormous scale of the violence, but the truth leaked out, due in no small part to courageous human rights defenders. Although he knew it would be dangerous, Umarov spoke out publicly about the massacre, criticizing the government.

The following September, Umarov made a trip to the US, seeking to drum up support for his party from the Uzbek diaspora and US officials. Much of his family had ties to the US, and his wife and four of his five children had already moved there, in part because they feared what was going on in Uzbekistan.

He was arrested a couple days after he returned. Another opposition party member called him to say that authorities were raiding the Sunshine Coalition headquarters. Umarov drove over. He heard loud voices inside the office, but when he banged on the door, no one would open it. As he walked away, he was grabbed and stuffed into a car. He quickly lost consciousness.

He woke up in a cell. There was blood on his jacket. He couldn’t fully form thoughts, a condition that lasted for days – he assumes he was injected with something. In the four months before his trial began, he was interrogated continuously, and often beaten on the head with a water bottle.

At one point before his trial, someone backed a car up to his cell window, turned the ignition and pumped in exhaust. Umarov lay down on the floor and pressed his mouth against the narrow slit between his cell door and the floor, gasping for air. His hearing was the next day. Because of the effect of the fumes, he said, he was unable to understand or follow along.

His trial began on January 30, 2006, President Karimov’s birthday. He was charged with creating an unsanctioned political organization as well as a litany of economic charges. “I hadn’t ever had any experiences with the criminal justice system prior to that,” Umarov said. “I had hope. I was a romantic.” But Umarov’s spirits sank as the judge ignored his lawyer and listened only to the prosecutor. He began to understand that he wasn’t going free. He figured he’d get two or three years, but then the sentence was read aloud – fourteen-and-a-half years.

He was sent to a prison colony, and shortly after his arrival was placed in solitary confinement. His cell was about 10 feet by 4 feet, with a concrete floor, an open toilet, and no sink. He was kept there for 17 days, but shortly after moving into the regular prison population, he was placed back in solitary. Prison officials told him he would be held there for 15 days, but each time his stay was almost up – he counted the days – officials would extend it for another two to three weeks. It happened again and again, his hopes of release constantly crushed. He was in solitary for 14 months.

“It’s very easy to go crazy in there,” he said. “You start dwelling on things, and you think about them again and again and again, and you feel you’re losing your mind.” He wasn’t allowed to write letters, and guards tore up in front of him the letters his family sent. The Red Cross managed to get him one letter from his wife, and her advice was to try to think about good things. He did his best to follow that advice.

During his first year in prison, his middle son took the train to see him 20 times, and 20 times was sent home without seeing his father.

His lowest point came in January 2008, when he was held for five days in the “monkey cage.” Guards took his hat, shoes and socks, only allowing him to wear light pants and a shirt. It was freezing. Only constant movement kept him warm. “I began to feel I was losing all my life energy, all my strength.”

Three years into his imprisonment, he was finally allowed to see his wife and his lawyer. But the torture had affected his mind to the point at which he barely recognized them.

Then, in 2009, with no notice or explanation, he was released. Umarov credits his freedom to strong international pressure, including a robust public campaign by human rights organizations and the efforts of diplomats, as well as to his worsening health.

“I had lost all hope I’d ever get out,” he said. He was in the prison hospital because his health had drastically deteriorated when he was told to report to the administration building. He assumed officials were going to lengthen his sentence or deny him amnesty. But when he walked into the room, a man he later learned was a judge called him Sanjar-aka, a term of respect. “I felt like that must be something good.” Within minutes he was freed. His family was expecting him. The US embassy had told them the news days earlier.

His wife and children had worked tirelessly for his release. They reached out to international human rights groups. They raised his case in the US Congress, including at the Helsinki Commission—a congressional body that monitors human rights in the former Soviet Union. And they contacted the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and the UN Human Rights Commission, the predecessor to the Human Rights Council.

After his release, he joined his family in Germantown, Tennessee, where they nursed him back to health. Even before his arrest, his family had ties to the United States, and both his daughters were born there. Since then, some of his children have married, and he has grandchildren born in the US.

“I have a lot of gratitude for the people who are friends and supporters in Memphis that made me feel welcome,” he said. “But on the other hand, my soul aches for Uzbekistan.”

He’s still pressing for reform in Uzbekistan.

“I want to see improvement in people’s lives” in Uzbekistan, he said. “There are so many problems that need to be solved in my country, and I want to work on them.”