Despite Russia’s January cold, hundreds of people packed the central square in Voronezh, an eight hour drive south of Moscow, for the planned LGBT rights protest. When Andrey Nasonov arrived, he saw a bus of riot police and several police cars, and quickly realized most of the crowd likely didn’t support LGBT rights. Only a dozen were activists, like him. In short order, he heard a scream and saw a rainbow flag. Thinking he was late for the protest, he began running towards the flag while unfurling his poster that read, “Stop hate.”

Spotting Andrey, bystanders began pelting him with snowballs. He saw a group of people break free from the crowd and sprint towards the activists. Two rushed him, pushed him to the ground and began kicking him in the head, neck, and shoulders. He curled into the fetal position. When he felt the kicking stop, he tried to get up, but lost consciousness. His boyfriend, Igor, tried to revive him, and he briefly came to, thinking that he needed to open his second “stop hate” poster, but it fell out of his hands. He fell down and began convulsing.

A growing numbers of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people have been attacked and harassed across Russia in the lead-up and aftermath of Russia’s June 2013 adoption of an anti-LGBT “propaganda” law - a law so vague that many Russians believe it outright outlaws homosexuality. A new Human Rights Watch report shows not only the day-to-day level of harassment experienced by LGBT people in Russia, but how authorities fail to protect LGBT people from harassment and attacks, often staged by radical nationalist groups.

Although he’s 25, Andrey looks even younger, and the thick black frames of his glasses add only a hint of gravity to his baby face. Between his youth and easy smile, it’s hard to believe what he’s been though - a suicide attempt, coming out of the closet to friends and family in a country known for intolerance towards gays, and being the target of thuggish, extreme Russian nationalists.

Andrey grew up in the small village, but when he moved to Voronezh, a city of about 1 million, for university in 2007 it became emotionally harder and harder for him to hide his sexual identity, to pretend he had a girlfriend and to lie about his life.

Two years after arriving in Voronezh, he visited the House of Human Rights, a building that houses several human rights organizations. After spending more time with the activists there, he realized he couldn’t keep living this way. He had to change something about his life. But instead of coming out of the closet, in his desperation he saw suicide as the answer.

Andrey attempted suicide shortly after his roommate’s girlfriend came into their dorm room, looked directly at Andrey, and told him her version of the biblical creation story, one in which God placed a sense of shame on men’s anuses. She looked at Andrey as she told the story, and he thought, she knows my secret. She barely knows me but she knows I’m gay. He lived in constant fear that people would uncover his homosexuality, that everyone would judge him, or worse.

Andrey locked himself in a dorm bathroom and took all the pills in the first aid kit. People banged on the door as he vomited blood. The medics arrived, and he survived. People asked him why he tried to end his life - was it a bad grade? Did he break up with his girlfriend? “I thought to myself, if only it were so simple”.

“Looking back, I feel like things that happened at that time were insignificant, not worth taking that step,” he said. “But I had this general fear that I would be alone, that I would lose everything, and be condemned to a life of loneliness” if he came out. He was also working through his own internal homophobia.

Shortly thereafter he came out of the closet.

He first told his female best friend. They were each in their own dorm rooms chatting online when he came out. She asked him to come out in the hallway.

“I was nervous, anxious, I didn’t know what to expect,” Andrey said, wiping tears from his face. “But in the hallway, she threw herself at me and hugged me.”

He began slowly telling others, and one Sunday, he posted his sexuality on his blog. The next day, most people didn’t even mention the post, some commended him on coming out, and only four or five people told him they didn’t hang out with “faggots.”

A few months later, he told his mother. His father left when he was four, and they were close, but he still feared her reaction. He came out by showing her a slideshow of a trip he took with his then-boyfriend to Moscow, and in some photos they were hugging and kissing. Afterwards, he called his boyfriend, and his mother asked to speak with him. On the phone, she told him that I know my son loves you very much and I love you very much because of that, Andrey said. They all cried, and Andrey thought, “This is my mom. This is what Mom is.”

“This changed my life,” he said. “I felt free. Both externally and internally. I was free to seek love, to build the life I wanted.”

In coming to accept himself, he realized that change was needed not only inside of him, but also around him, in his environment. He decided to help others who were struggling to come out, and, together with a close lesbian friend, began organizing LGBT events.

But with the passage of several regional anti-gay laws, it became clear the ground was shifting. When the federal anti-gay law was proposed in 2013, he became worried - would the government be able to lock him up for being gay? He felt the same sense of fear he had before coming out.

Because of this, he began taking part in riskier public protests - where people could recognize and target him.

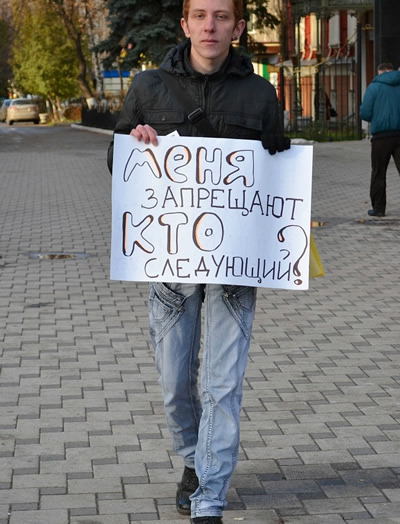

In November 2011, a friend photographed him at a protest holding a sign saying, “They are banning me, who is next?” but after Andrey posted it on his social media page, radical nationalists reposted it on their sites.

Everything came to a head during a protest against the anti-LGBT law held on January 20th, 2013. It began with threats posted to popular Russian social media site VKontakte after he posted the protest date. He’d been threatened before, but these were much more personal. “I will come. I will come and kill you. When all [demonstration] is over and you’re on your way home, I will catch one of you and will smash your head,” one read. Others were similar.

Having registered the protest with authorities, they filed a complaint about the threats with the police. In response, the police asked them to move the event, saying they couldn’t ensure the protesters’ safety. The police treated them with contempt, Andrey said, saying, we understand that you’re going to get beaten there, we hope you understand that as well.

The evening before the protest, Andrey published a blog post titled “I will go to the Voronezh demonstration against hate.” He attached an audio recording of his mother who spoke directly to Russian authorities, saying that she loved her son, that she accepted him how he was, and that they please shouldn’t hurt him. Later that night, he received dozens of messages of support - both from Russia and abroad. On the day of the protest, whenever he felt fear, he thought of those messages to gather courage. He had made a promise to those people, he told himself, and he would keep it.

At 2 p.m., his boyfriend of two years, Igor, drove them to the protest. They saw the packed square, Andrey ran towards the rainbow flag, and was beaten so badly he began convulsing, despite having no history of epilepsy.

His boyfriend dragged him towards a police car, and he was ultimately driven to a rented apartment - a safety measure - where he recovered.

They filed an assault case, but the police suspended the investigation saying they couldn’t identify any of his attackers - despite the assault being captured on video. It was Andrey’s first dealings with Russia’s justice system, he was deeply disappointed when he realized he would get no justice from the police and the courts. The police wanted to make him guilty, like he was the problem - if he had just not protested, they said, the assault wouldn’t have happened.

The protest was well publicized, and Andrey lived in constant fear of nationalists coming for him. He bought glasses with thick black rims and began wearing hats. He took cabs everywhere, avoiding public transportation. He didn’t leave the house at night. He felt desperate, realizing how extremely hard it could be to change something, no matter how much you fight for it.

In 2014 he left Russia. He is now applying for asylum in the US. Igor came with him.

But being an asylum seeker is also challenging, as you can’t work for roughly five months after applying for asylum. Food and housing are hard to find without an income, and they are living with an American family. But he is confident that things will get better. When he visited New York City, he wore a backpack with a rainbow on it. At one point, he heard people behind him say “faggot” and laugh. It made him uncomfortable, but he also realized that the United States isn’t perfect, and LGBT activism is also relevant there.

He plans to work as a journalist, and in August and September, he staged several one-man demonstrations in front of the White House, designed to educate Americans on the issue of LGBT rights in Russia.

At the same time, he feels an enormous sense of freedom and safety living in the United States - it’s a sense of freedom similar to the days after he first came out. In October, after four years together, he and Igor were married in Washington, D.C. “It was a very important decision to get married,” he said. “I’m so grateful to all Americans who fought for gay rights, because they gave us this incredible opportunity to get married, something we couldn’t even dream of in Russia.”