Summary

Workers in Cambodia’s garment factories—frequently producing name-brand clothing sold mainly in the United States, the European Union, and Canada—often experience discriminatory and exploitative labor conditions. The combination of short-term contracts that make it easier to fire and control workers, poor government labor inspection and enforcement, and aggressive tactics against independent unions make it difficult for workers, the vast majority of whom are young women, to assert their rights.

Recent events linked to labor rights in Cambodia have attracted international attention. There have been repeated episodes of workers fainting on the job. In January 2014, police, gendarmes, and army troops brutally crushed industry-wide protests for a higher minimum wage. And the authorities have introduced more burdensome union registration procedures.

Lack of accountability for poor working conditions in garment factories is at the center of troubled industrial relations in Cambodia. This report—based on interviews with more than 340 people, including 270 garment workers from 73 factories in Phnom Penh and nearby provinces, union leaders, government representatives, labor rights advocates, the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia, and international apparel brand representatives—documents those working conditions, identifies key labor rights concerns voiced by workers and labor rights advocates, and details the failure of Cambodia’s labor inspectorate to enforce compliance with applicable labor laws and regulations.

The report also examines the role of the Better Factories Cambodia, an International Labour Organization factory monitoring program launched in 2001.

The Cambodian government is primarily responsible for ensuring compliance with international human rights law, including labor rights. However, international clothing and footwear brands have a responsibility to promote respect for workers’ rights throughout their supply chains, including both direct suppliers and subcontractor factories. As documented in this report, many brands have not fully lived up to these responsibilities due to poor supply chain transparency, the absence of whistleblower protections, and failure to help factories correct problems in situations where that is both possible and warranted. Some brands remain nontransparent about their policies and practices, withholding information on issues of concern, while other brands notably provide information and voluntarily subject themselves to greater public scrutiny and demonstrate a commitment to improved policies.

Ly Sim passed productivity tests and was promoted to team leader in the sewing division of her factory in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital, in 2012.[1] A few months later, Sim, in her late 20s, became visibly pregnant. Factory management demoted her and cut her pay. When she and other workers protested with the help of the factory union, they were summarily fired.

Devoum Chivon helped form a union in the factory where he worked and was elected president in late 2013. Within days of being notified about the new union leaders, the factory managers pressured Chivon to quit the union and offered him a bribe, which he refused. The management then criticized the newly elected union leaders’ job performance and fired them.

Leouk Thary, in her 20s, worked in a garment factory on four-month short-term contracts that her managers repeatedly renewed. One day in November 2013 she had a bad nosebleed and sought exemption from overtime work. Even though her managers told her to continue working, she went to see a doctor. She returned the next day with a medical certificate requesting sick leave for nose surgery. She was fired immediately.

Garment and textile exports are crucial for the Cambodian economy. In 2013, Cambodian global exports amounted to roughly US$6.48 billion, of which garment and textile exports accounted for $4.96 billion; export of shoes accounted for another $0.35 billion. In 2014, garment exports reportedly totaled $5.7 billion. The industry is a major source of non-agrarian employment, particularly for women. Women dominate Cambodia’s garment sector, making up an estimated 90 to 92 percent of the industry’s estimated 700,000 workers. These numbers do not include the many women engaged in seasonal home-based garment work.

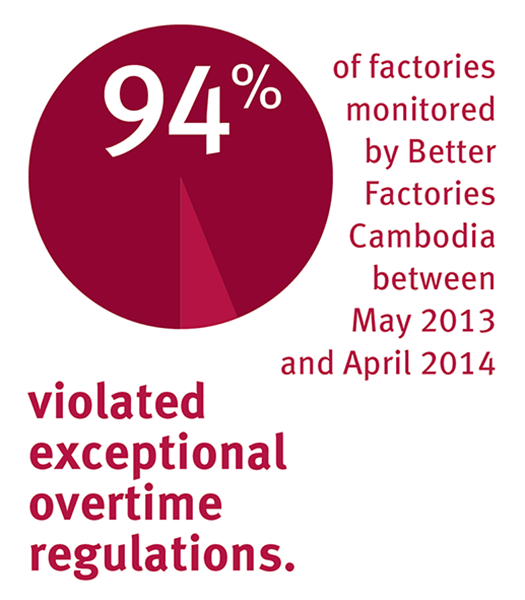

Cambodia enacted a strong labor law in 1997. But its enforcement remains abysmal, in large part due to an ineffective government labor inspectorate. Better Factories Cambodia (BFC), a third-party monitor that focuses primarily on factories with an export license, helps fill the monitoring gap in export-oriented factories and a few subcontractor factories but cannot be a substitute for a strong labor inspectorate. Some of the worst working conditions in Cambodia, however, are in smaller factories that lack such licenses and work as subcontractors for larger export-oriented factories. Because BFC’s mandatory monitoring is limited to export-oriented factories, its monitoring services extend to such subcontractors only where brands and factories identify them and pay for BFC services.

Hiring practices also influence labor law compliance. In many factories, managers repeatedly use short-term contracts beyond the legally permissible two years as a way of controlling workers, discouraging union formation or participation, or avoiding paying benefits. This practice has become a key point of contention, fueling tense industrial relations.

Some factories, especially those working on a subcontracting basis for larger factories, also employ workers on a casual daily or hourly basis. These workers face additional barriers to unionizing and filing complaints about working conditions. Some factories also outsource work seasonally to home-based workers, whose work remains poorly regulated and invisible in monitoring processes.

Even though long-term Cambodian workers, as well as limited-term workers employed full-time for 2 consecutive periods of 21 days or more, are entitled to most of the same basic workplace benefits under the law, casual workers and those on short-term contracts risk relatively easy retaliation by management through dismissal or contract non-renewal. They are more likely to be denied benefits or face other discrimination, but have less access to reporting mechanisms and union support.

Contrary to claims by the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia (GMAC) that factories using repeated short-term contracts are “black sheep,” BFC reported that the number of surveyed factories complying with the two-year rule on short-term contracts (called fixed-duration contracts or FDCs in Cambodia) dropped from 76 percent in 2011 to 67 percent in 2013-2014. Since 2011, BFC has consistently found that nearly a third of all factories used FDCs to avoid paying maternity and seniority benefits.

Labor Rights Abuses

Human Rights Watch documented labor rights abuses in both export-oriented factories and subcontractor factories in Cambodia. These include forced overtime and retaliation against those who sought exemption from overtime, lack of rest breaks, denial of sick leave, use of underage child labor, and the use of union-busting strategies to thwart independent unions. In addition, women workers faced pregnancy-based discrimination, sexual harassment, and denial of maternity benefits.

Forced Overtime

Human Rights Watch discussed concerns regarding overtime work with workers in 48 factories. Cambodia’s Labor Law limits weekly (beyond 48 hours) overtime work to 12 hours (2 hours per day). Workers generally preferred some overtime work to supplement their incomes, but complained that factory managers threatened them with contract non-renewal or dismissal if they sought exemption from doing overtime work demanded of them. Most of the workers we interviewed performed overtime work far exceeding the 12-hour weekly limit.

In at least 14 of the 48 factories, Human Rights Watch documented recent examples of management retaliation against workers who did not want to do overtime work, including dismissal, wage deductions, and punitive transfers of workers from a monthly minimum wage to a piece-rate wage where income depends on the number of garments individuals produced. For example, in November 2013, a factory dismissed 40 workers for refusing to do overtime until 9 p.m. It subsequently reinstated half the workers, however, after protests and negotiation with an independent union.

Factories usually assign garment workers daily production targets. Many workers—from both large factories directly supplying to international brands and small, subcontractor factories—complained that management pressure to meet production targets undermined their ability to take breaks to use washrooms, rest, or drink water. Some workers also recounted how factory managers promised small cash incentives in the range of 500 to 3000 riels ($0.12 to $0.75) a day to meet production targets, but at times did not pay these promised incentives. In other cases, workers said they made upward revisions to targets to compensate for increases in statutory minimum wages. Many workers reported being subject to invectives, and a few said they were physically intimidated if perceived as being “slow.”

Key Concerns for Women Workers

Pregnancy-related discrimination and sexual harassment at the workplace were two key concerns for women workers in Cambodia.

Discrimination against pregnant workers took different forms at different stages of the employment process, including during hiring, promotion, and dismissal, and included failure to make reasonable workplace accommodations to address the needs of pregnant workers. Human Rights Watch documented one or more of these problems in at least 30 factories. Cambodia’s Constitution and the Labor Law forbid dismissals based on pregnancy. The Labor Law also guarantees all pregnant workers three months’ maternity leave irrespective of the duration of service and maternity pay for workers with a year’s uninterrupted service.

Workers said that factory managers refused to hire visibly pregnant workers, echoing findings from a 2012 International Labour Organization (ILO) report on gender equality in garment factories. Pregnant women on short-term contracts were unlikely to have their contracts renewed, allowing their managers to avoid providing maternity benefits.

Factory managers also often failed to make reasonable accommodations for pregnant workers such as more frequent bathroom breaks or lighter work without loss of pay. Many found it difficult to work long hours, including overtime, without adequate breaks to rest or use washrooms. Many interviewees said workers often resigned from factories as their pregnancy progressed because managers harassed them for being “slow” and “unproductive.”

Contrary to a ruling by the Arbitration Council, a dispute resolution forum, workers from some factories found it difficult to take medically approved sick leave and were denied their entire month’s $10 attendance bonus for missing a few hours or single day of work. The attendance bonus is an important part of workers’ remuneration and workers who do not attend work, as attested by medical professionals, are entitled to a pro-rated share of the bonus. This especially had an impact on pregnant workers who felt unable to take sick leave.

Another issue affecting women is sexual harassment at the workplace. Workers, independent union representatives, and labor rights activists said that sexual harassment in garment factories is common. The 2012 ILO report found that one in five women surveyed reported that sexual harassment led to a threatening work environment.

The forms of sexual harassment that women recounted include sexual comments and advances, inappropriate touching, pinching, and bodily contact. Workers complained about both managers and male co-workers.

Cambodia’s Labor Law prohibits sexual harassment but does not define it. Nor does it define sexual harassment at the workplace, outline complaints procedures, or create channels for workers to secure a safe working environment.

I sit for 11 hours and feel like my buttocks are on fire. We can’t go to the toilet.

—Keu Sreyleak (pseudonym), garment worker, group interview, factory 60, Phnom Penh, December 7, 2013

It doesn’t matter whether you are pregnant or not—whether you are sick or not—you have to sit and work. If you take a break, the work piles up on the machine and the supervisor will come and shout. And if [a pregnant] worker is seen as working “slowly” then her contract will not be renewed.

—Human Rights Watch interview with Po Pov (pseudonym), worker, factory 3, Phnom Penh, November 22, 2013

A worker in my team wanted to leave early. We have to do overtime work till 9 p.m. every day. She had her period and had severe cramps and so requested that she will do overtime work only till 6 p.m. They shouted at her and said they would reduce $7 from her wages and not renew her contract. So she didn’t leave and continued to work.

—Human Rights Watch interview with Kong Chantha (pseudonym), worker, factory 9, Phnom Penh, November 30, 2013

There is one male worker who harasses me a lot. Each day it’s something different. One day he says “Oh your breasts look larger than usual today.” On another day, he says, “You look beautiful in this dress—you should wear this more often so I can watch you.” There are others who purposely brush past us or pinch our buttocks while walking. Sometimes I feel like complaining. I don’t like it at all. But who do I complain to?

—Human Rights Watch interview with Keu Sophorn (pseudonym), worker, factory 18, Phnom Penh, December 5, 2013

If we have taken three days [sick] leave, then they deduct $20 from what we have earned. They say to us: “If you want to earn that money back, work more.” We only bring medical certificates because we feel they will scream at us less.

—Human Rights Watch interview with Chhau San (pseudonym), worker, factory 15, Kandal province, November 24, 2013

Anti-Union Discrimination

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch found evidence of union-busting activity in at least 35 factories in Cambodia since 2012. Relevant practices included keeping long-term workers on short-term contracts to discourage their participation in union activities, shortening the length of male workers’ contracts, dismissing or harassing newly elected union representatives to prevent formation of independent unions, and encouraging pro-management unions.

All of the independent unions interviewed for this report—Coalition of Cambodian Apparel Workers Democratic Union (CCAWDU), National Independent Federation of Textile Unions in Cambodia (NIFTUC), Collective Union of Movement of Workers (CUMW), and Cambodian Alliance of Trade Unions (CATU)—said as soon as workers initiated union-formation procedures, factory management would dismiss union office-bearers or coerce or bribe them to resign, thwarting union formation.

Workers formed a union affiliated to CCAWDU and notified factory management in late 2013. Soon after being notified, the management called the elected representatives and presented them with the option of giving up their union positions for promotions and a hike in wages. When the president and vice president refused to accept the offer, they were dismissed. CCAWDU supported the two workers in bringing a claim before the Arbitration Council, a dispute resolution body, which ruled in favor of the workers in December 2013. At this writing the factory had yet to comply with the ruling.

Cambodian officials with the Ministry of Labor and Vocational Training (the “Labor Ministry”) have also introduced bureaucratic obstacles to union formation. They have delayed licensing unions for months since December 2013. They also now require union leaders to produce a certificate from the Ministry of Justice stating the worker in question has not been convicted of any criminal offense. Independent union leaders told Human Rights Watch that these changes would prolong the union registration process, giving factory management more time to take retaliatory measures against workers temporarily leading the union.

Leaders from independent union federations alleged that Labor Ministry officials acted arbitrarily against independent unions, rejecting their applications citing inconsequential typographical errors. Such practices violate Cambodia’s international obligations to respect and protect workers’ freedom of association and right to organize.

In 2014, the Labor Ministry also revived an earlier draft trade union law, citing a multiplicity of unions and “fake unions” as problems that the government needed to address. The draft law curbs workers’ freedom to form a union by introducing a high threshold for the minimum number of workers needed to support union formation and gives overarching powers to the Labor Ministry to suspend union registration without any judicial review.

Subcontracting and the Role of Brands

The labor rights concerns, discriminatory practices against women, and union-busting actions described above were particularly pronounced in subcontractor factories. Many factories directly supplying to international brands subcontract to other, often smaller, factories that are subjected to little or no monitoring and scrutiny. At least 14 of the 25 subcontracting factories Human Rights Watch examined appeared not to be monitored by BFC— despite operating and producing for international brands for several years most of the factories did not appear on BFC’s January 2015 factory monitoring list.

The working conditions in the subcontractor factories we investigated were usually worse than those in larger factories. The former were more likely to use casual hiring arrangements and issue repeated short-term contracts. Because many of these factories are small and physically unmarked—and often not monitored in any way—independent union leaders said it was more difficult to unionize for fear that factories would briefly suspend operations, laying off all the workers in the process. Women in these factories often said they were denied benefits including maternity leave and maternity pay.

Very few international clothing brands disclose the names and locations of their production units—suppliers and subcontractors—even though disclosures can help workers and labor advocates to alert brands to labor rights violations in factories producing for them. Such disclosure is neither impossible nor prohibitively expensive and there appears to be no valid reason for brands to withhold this information. For example, Adidas wrote to Human Rights Watch that it first started privately disclosing its supplier list to academics and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in 2001 and moved to a public disclosure system in 2007. In 2014, Adidas moved to a biannual disclosure. H&M started publicly disclosing its supplier list in 2013 and updates it annually.

Other brands operating in Cambodia, including Gap, Marks and Spencer, and Joe Fresh, have not disclosed their suppliers publicly. Marks and Spencer wrote to Human Rights Watch stating that the brand will make its global suppliers list public by 2016. In October 2014, a Gap representative told Human Rights Watch that the brand is examining the implication of such disclosure for its business. Loblaw (owner of Joe Fresh) and Armani do not disclose their global supplier list and did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s inquiries on the subject.

Some suppliers may farm out their work to subcontractors without brand authorization. Dealing with unauthorized subcontracting is complex. But international apparel brands can do much more to help fix labor rights abuses in unauthorized production units brought to their attention.

While brands depend on workers and independent unions to alert them to unauthorized subcontractors in their supply chain, none of the brands except Adidas provided Human Rights Watch with evidence of a process for whistleblower protection to mitigate possible management retaliation against workers who raise concerns. In October 2014, Adidas introduced a written anti-retaliation clause in its grievance reporting system whereby workers can report retaliation, seek investigation, and obtain redress.

There is a need for much more effective whistleblower protection for workers in factories. For example, workers told Human Rights Watch that after they provided information on subcontractors to external monitors in mid-2012, factory managers filed false complaints of theft against one worker and compelled others to testify against the worker, threatening dismissal if they did not obey. Several workers were dismissed.

Brands also sometimes issue stop-production orders as soon as unauthorized subcontracts are brought to their attention, even in situations where prompt remediation in the subcontractor factory is feasible. This hurts worker incomes in the affected subcontracting factories, creating a disincentive for workers to report abusive conditions.

As set out in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, businesses have a responsibility to minimize human rights violations in their supply chains irrespective of whether they directly contributed to the violation, and to adequately address any abuses that do take place. In order to encourage workers to report abusive conditions and to avoid negative impacts on workers’ jobs and wages, Human Rights Watch recommends that, where feasible and appropriate, international brands give suppliers in Cambodia adequate opportunities to remedy problems before terminating their business relationships.

H&M Case Study

Factory 1, a direct supplier to H&M, subcontracts work to many smaller factories. Team leaders in factory 1 allegedly told workers that they should work Sundays, their day off, at an unauthorized subcontractor to help meet production targets and supplement their incomes because factory 1 was not going to provide them with any opportunities for overtime work. In their Sunday and public holiday work at the unauthorized subcontractor, they worked on H&M garments but without overtime pay. By outsourcing the work to a subcontractor, factory 1 was able to bypass labor law provisions governing overtime wages and a compensatory day off for night shifts or Sunday work.

Human Rights Watch also spoke to five workers from a subcontractor factory supplying factory 1. Workers knew their factory was “sharing business” and was producing for H&M because the managers had discussed the brand name and designs with them. When they had rush orders, the workers report that they were not permitted to refuse excessive overtime, including on Sundays and public holidays, and were not paid overtime wage rates.

The workers in the subcontractor factory considered organizing a union but were afraid of retaliation if they did so. They also reported that the factory employed some children below the legally permissible age of 15, and that those children were made to work as hard as the adults.

Marks and Spencer Case Study

Factory 5 is a small subcontractor factory that was producing for Marks and Spencer and received regular orders from one or two direct suppliers at least until November 2013, when we spoke to workers there.

Workers told Human Rights Watch that they received three-month fixed term contracts, which were extended beyond two years. Factory managers allegedly dismissed workers who raised concerns about working conditions or chose not to renew their contracts. Issues raised by workers that we interviewed included discrimination against pregnant workers, lack of sick leave, forced overtime, and threats against unionizing.

Joe Fresh Case Study

In 2013, factory 4 produced for Marks and Spencer, Joe Fresh, and other international brands and periodically subcontracted work to other factories.

Workers from two subcontractor factories that produced for factory 4 told Human Rights Watch that they were hired on three-month short-term contracts repeatedly renewed beyond two years. Workers reported a number of labor law violations, including wages lower than the then-statutory minimum of $80, forced overtime without overtime pay rates, absence of maternity pay for eligible workers, and disproportionate deductions of their monthly attendance bonus for a single day of sick leave. The factories did not have a legally mandated infirmary even though there were more than 50 workers in each factory. Workers said that the subcontractor factories also employed children and hid them when there were visitors.

Gap Case Study

Factory 60 is a small subcontractor factory that periodically produced for Gap until at least December 2013, when Human Rights Watch spoke to workers there.

Most of the factory workers we spoke with had worked there for more than two years and were repeatedly issued short-term contracts. They did not receive benefits accorded to long-term workers. They said the managers of the factory had taken a hostile approach to unions and workers were scared of forming a union or openly organizing within factory premises.

The factory allegedly discriminated against pregnant workers in hiring. Workers reported that women who gave birth did not receive maternity pay even when they had worked at the factory for more than a year. The workers described seeing a fellow worker dismissed for refusing overtime work. Even though the factory employed more than 300 workers, there was no infirmary or nurse in the factory.

A Failure of Government Accountability

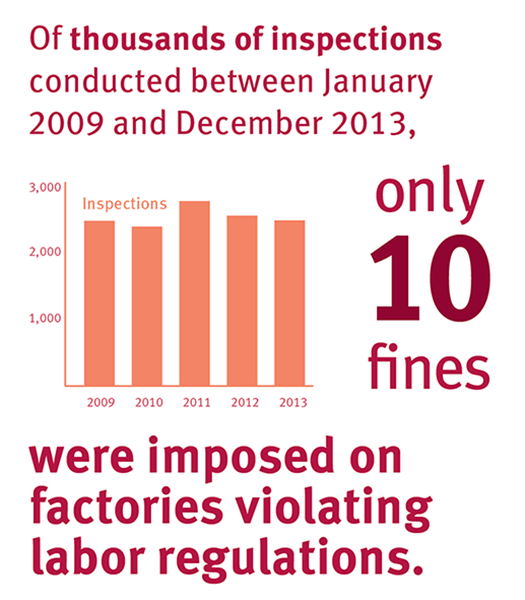

The Cambodian government has obligations under international law to ensure that the rights of workers are respected, and that when abuses occur, they have access to redress. Irrespective of whether a factory is a direct supplier or a subcontractor to an international purchaser, its working conditions should be monitored by the government’s labor inspectorate, which is tasked with enforcing the Labor Law and has powers to initiate enforcement action. But to date, Cambodia’s labor inspectorate has been wholly ineffectual, and the subject of numerous corruption allegations.

In 2014, the Labor Ministry created integrated labor inspectorate teams to streamline factory inspections. It committed itself to providing the teams with better training (in cooperation with the ILO) to investigate and report factory working conditions accurately. While these are welcome preliminary steps, it is clear that many additional measures are needed to improve government rigor in monitoring factory working conditions.

Corruption is a key issue that affects the credibility of the labor inspectorate. Two former labor inspectors independently told Human Rights Watch about an “envelope system” where factory managers thrust an envelope with money to visiting inspectors in exchange for favorable reports.

The Labor Ministry’s own data shows its enforcement track record is poor. For example, official data provided to Human Rights Watch shows that between 2009 and December 2013, labor authorities imposed fines on only 10 factories and initiated legal proceedings against 7 factories. Yet, in 2013 the ministry had found that at least 295 factories (not all garment factories) had violated the Labor Law. In December 2014, Labor Ministry officials told Human Rights Watch they had fined 25 factories in the first eleven months of 2014. In February 2015, Khmer-language media reported that in 2014 the labor inspectorate had taken action against 50 factories without specifying details. Furthermore, even though ministry officials insisted that their investigators found labor rights violations in the 10 low-compliance factories named in Better Factory Cambodia’s Transparency Database, they could not provide any information about resulting enforcement action in accordance with a 2005 circular issued by the Cambodian government, which empowers the Ministry of Commerce to cancel export licenses.

Enhancing Better Factories Cambodia

Particularly given the weakness of the labor inspectorate, BFC fills a critical monitoring role in Cambodia’s garment industry. Its factory-level, third party monitoring reports can be purchased and used by international apparel brands for their audits. These reports are behind a pay-wall for all others except the factory itself. Following criticism about the lack of public disclosure of its findings, BFC launched a Transparency Database in March 2014 despite significant resistance from the Cambodian government and the manufacturers represented by GMAC.

While BFC’s reports enjoy widespread credibility internationally, many Cambodian workers we spoke with expressed a lack of confidence in BFC monitoring and said managers coached or threatened workers ahead of external visits. Workers recounted how factory managers made announcements using the public announcement system, sent messages through team leaders, or called workers and warned them not to complain about their working conditions to visitors. In one case, a worker said that factory managers offered to pay money to workers who gave positive reports.

In addition to being coached, workers were told to prepare for “visitors.” They were told to remove piles of clothes from their sewing machines and hide them and were given gloves and masks just before visitors arrived. Lights and fans that were normally switched off were turned on, drinking water supplies were refilled, and underage child workers were hidden.

Before ILO comes to check, the factory arranges everything. They reduce the quota for us so there are fewer pieces on our desks. ILO came in the afternoon and we all found out in the morning they were coming. They told us to take all the materials and hide it in the stock room. We are told not to tell them the factory makes us do overtime work for so long. They also tell us that if [we] say anything we will lose business.

—Human Rights Watch group interview with Nov Vanny (pseudonym) and Keu Sophorn (pseudonym), workers, factory 18, Phnom Penh, December 5, 2013

Our factory started using the lights this year. As soon as the security guard finds out there are visitors and tells the factory managers, the long light near the roof will come on…. And the group leaders will start telling all the workers to clean our desks; we have to wear our masks, put on our ID cards, and cannot talk to visitors. Everyone knows this is a signal.

—Human Rights Watch interview with Leng Chhaya (pseudonym), worker, factory 32, Phnom Penh, November 29, 2013

BFC takes a number of measures aimed at counteracting management coaching. BFC’s factory monitoring methods include unannounced visits, a 30-minute outer limit on the time monitors can be made to wait outside the factory when they arrive unannounced, monitors’ discretion to convene a fresh group of workers if the first group appears to be coached, and interviews with some workers off-site. Workers told Human Rights Watch, however, that they still need a direct mechanism to report labor rights violations to BFC.

A significant deficiency is that BFC’s factory reports are not available to workers individually or even to unions, making it practically impossible for workers to verify whether the BFC reports accurately portray actual working conditions in any given factory.

The garment industry plays a critical role in Cambodia’s economy, including by employing a large number of women. The detailed recommendations below to the Cambodian government, garment factories, international brands, BFC, unions, and international donors aim to improve labor practices so that Cambodia can be a model for good working conditions for garment workers.