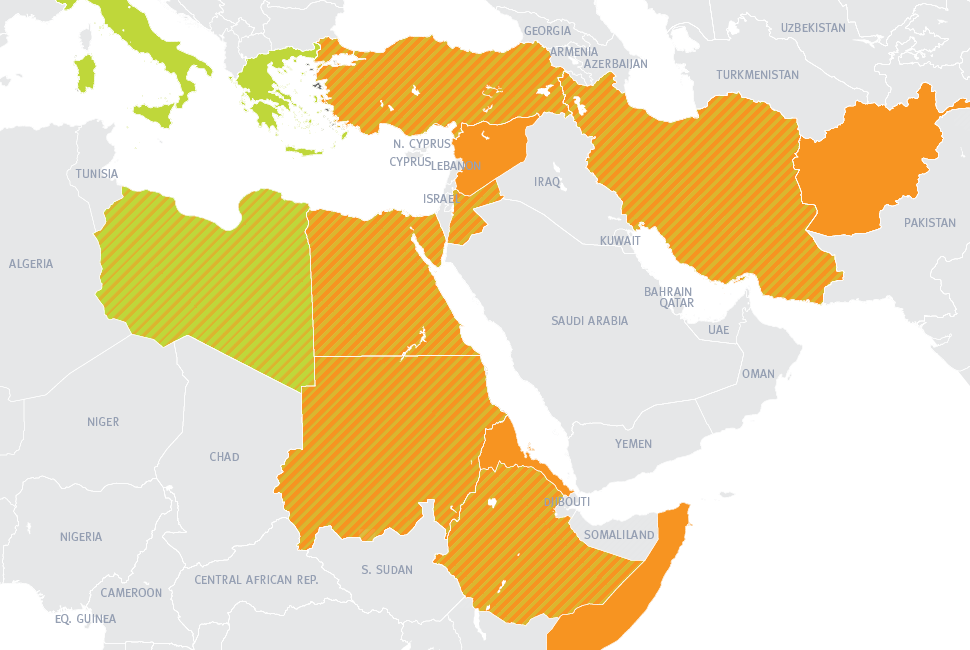

Migration journeys to the European Union based on Human Rights Watch interviews

Tens of thousands of migrants and asylum seekers are crossing the Mediterranean, the deadliest migration route in the world, to reach the European Union. Over 60 percent of those making the journey come from Syria, Somalia, and Afghanistan, countries torn apart by war and generalized violence, or from Eritrea, which is ruled by a highly repressive government. This map shows the routes described by people interviewed by Human Rights Watch for The Mediterranean Migration Crisis: Why People Flee, What the EU Should Do.

Eritrea to Italy via Libya

Open-ended, often abusive, and grossly underpaid military conscription is one of the main drivers of flight from Eritrea, a country ruled by one of the most repressive governments in Africa.

Tadesse, 18, traveled from Eritrea to Sudan and then Libya before crossing to Italy. He wanted to escape indefinite military conscription and abuse.

“Why would I want to be a soldier for my life? I want to have a normal life, so I tried to escape before military training. I was caught at the border and thrown in a shipping container for five months. They used to tie us up and leave us in the hot sun for days on end as punishment. Then they took me to Nakfa for four months military training. After two months I escaped, and managed to get across the border into Sudan. I will never go back, not as long as there is military service.”

Human Rights Watch interview with Tadesse (pseudonym), Catania, Italy, May 16 2015.

Asmeron, 21, said his father was imprisoned for a week in October 2014 after Asmeron refused to return to military service and fled first to Ethiopia, then Sudan, and finally Libya before crossing to Italy.

“The problem is that the youngest to the oldest have to do military service. All the young people are leaving because of military service. With no rights, it’s difficult to stay in the country.”

Human Rights Watch interview with Asmeron, Lampedusa, Italy, May 15, 2015.

Syria to Greece via Turkey

Hannan, 47, and Ghazal, 55, reached the Greek island of Lesbos the night before we met. They left Aleppo with their three adult children, including Karan, their youngest, who has developmental disabilities. Speaking over each other as couples will, they told us:

“We left Syria two months ago… We decided to leave from Aleppo for our lives. We had a good life there…Now, because of the war there are no hospitals, no doctors. My son needs very important medical care… And groups fighting each other. They are all the same, they want to kill. There is no difference. Our people are dying…There is no electricity, no water, bombs, attacks. It's like being at the wrong place, the wrong time. In all Aleppo people die in the street. Maybe an attack will happen and we will die.”

Ghazal was abashed that he broke the law to reach Greece.

“The worst was yesterday night. We came here illegally. It's the first time in my life I did something illegal. I was forced to do this kind of journey because I didn't want to put my family in danger.”

Human Rights Watch interview Hannan and Ghazal, Lesbos, Greece May 22, 2015.

Libya to Italy

Libya has long been a destination country for sub-Saharan Africans looking for work, as well as a transit country for those attempting to reach the EU. Increasing lawlessness and generalized violence have convinced many who originally traveled to Libya for work to attempt the sea crossing to the EU.

Nero, a 28 year old Nigerian man, fled from Libya to Italy to escape violence from civilians and police. He had gone there in 2013 for work.

“If you walk on your legs, they attack you. If you take a taxi, they drive you to the desert and rob you. This happened to me four times…The police arrested me at a checkpoint and put me in prison for four months, in Zawiya. They took my money, my contacts. My friends didn’t know what had happened to me. Life in prison was hard. They beat me with a hose. They beat some people to death. Two of my roommates, a Nigerian and a Somali man, they died from the beatings.”

Human Rights Watch interview with Nero, Lampedusa, Italy, May 13, 2015.

Iran to Greece via Turkey

The inhospitable situation for Afghan refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants in Iran, and the inability to return to Afghanistan because of security risks, has pushed some to make the difficult journey to Europe.

A 15-year-old Afghan boy said his parents had borrowed money to send him out of Iran towards a better, freer future:

“I was born in Iran, two years after my parents left Kabul after the Taliban took power. In Tehran, we lived like small animals in our home. We were afraid to go out. We had no documentation. You could not walk in the streets. If they catch you, they will deport you to Afghanistan. Refugees are also not allowed to study in university in Iran, so I decided for my future to go somewhere else. I didn’t want to go back to Afghanistan. Every day we heard about suicide bombings and someone or some group of people losing their life, even in Kabul. Everyday there is a bomb blast. If I went back there, I imagine a dark future. If I have a chance to continue my studies, I want to become a doctor or an engineer. I just want to have a chance to continue my education, nothing more.”

Human Rights Watch interview with 15-year-old boy, Lesbos, Greece, May 20, 2015.

Afghanistan to Greece via Turkey

Attacks by the Taliban and other insurgents, increasing insecurity, and restrictions on freedom of movement have led many Afghans to attempt the journey to the EU.

Mubarek traveled from Parwan, in Northern Afghanistan, to Greece with his wife and three children in early 2015 to escape the Taliban.

“The Taliban was very active in our area. They kidnapped one of my relatives, and when they found out he was in the army…they killed him…We had other problems with the Taliban. They would ask for money and ask us to join forces to fight the government. Every day the Taliban would take people and children for suicide bombings. I was worried about my children, my sons, that they would be forced to become suicide bombers.”

Human Rights Watch interview with Mubarek (pseudonym), Lesbos, Greece, May 21, 2015.

Rabea, an elementary school teacher and university student in her twenties said she and her husband decided to leave Afghanistan after two men tried to kidnap their two-year-old daughter. She had received threatening phone calls.

“They told me if I went to the university or to teach, they would kill me or abduct my daughter.”

Human Rights Watch interview with Rabea, Samos, Greece, May 24, 2015.

Somalia to Italy via Libya

According to official Italian statistics, Somali children comprised the third largest national group of unaccompanied children who reached Italy by sea in 2014.

Ismael, a 15-year-old Human Rights Watch interviewed in Italy in May 2015, described why he left his country with a litany of problems:

“There is no security, no hope, no health, no water. No peace since I was born.”

Human Rights Watch interview with Ismael, Italy, May 12, 2015.

Abdishakur, a 19-year-old from Mogadishu, embarked on his four-month journey to Italy with a friend.

“There are so many problems. Al-Shabaab, they come and blow up houses, mosques. I don’t know why. I’m in school, but if they [Al-Shabaab] blow up something somewhere, the school closes. Out of five days, I learn only two days…Al-Shabaab approach guys like me to convert them, get them to blow themselves up. If they come, you do the mission and you die. If you don’t, they kill you.”

Human Rights Watch interviews with Abdishakur, Lampedusa, Italy, May 13, 2015.

Fahad, 18, also from Mogadishu, spent one month in an Ethiopian prison and another six months in the Libyan desert on his way to Italy.

“I was in a car with a lot of people, at the Sudan/Ethiopian border. The driver tried to speed away from Ethiopian soldiers, they shot at the car. Three people died from bullet wounds. I spent one month in prison. It was smelly, not clean. They wanted to deport me to Somalia, but I escaped. I made contact with a smuggler and then was one month in Sudan waiting for others to join the group. They took us to the desert in Libya. I stayed there six months because my family didn’t have the money [to pay the smugglers]. We ate only once a day. There was a lot of beating, with stones, sticks, and pipes. The smugglers killed two people who were trying to escape. I saw it. It was a boy and a girl, running away, and the men with guns shot at them. They shot them in the belly, everything came out.”

Human Rights Watch interviews with Fahad, Lampedusa, Italy, May 13, 2015.

Syria to Greece via Turkey

Civilians continue to pay a heavy price in Syria’s increasingly bloody armed conflict. Turkey hosts over 1.7 million Syrian refugees. From there, many cross the Aegean Sea to Greek islands.

Mohannad, a 30-year-old lawyer from Raqqah, had been working as a volunteer with an organization combating violence against women. But the constant threat of violence, including from ISIS, compelled him to leave Syria:

“What is happening in Syria is an international crime. There, they never make the difference between civilian and armed forces. And it’s not just [Syrian President Bashar al-] Assad. There are groups such as Daesh [ISIS] doing the same…Syria has become a country that is broken…I left two months ago because I’m an activist and I’m afraid they would arrest me and beat me a lot…My only dream is to go to another European country to show the world what is happening there. I have a big file with the names of victims. Women who have been raped, a list of names of people who have died.”

Human Rights Watch interview with Mohannad (pseudonym), Lesbos, Greece, May 21, 2015.

A 10-year old Syrian boy from Deir ez-Zur said his school was bombed.

“I felt like my future had been destroyed.”

His father added,

“We can’t allow children to go out of the house, so how can we allow them to go to school?”

Human Rights Watch interview, Lesbos, Greece, May 21, 2015.